2. 湖南文理学院生命与环境科学学院, 水产高校健康生产湖南省协同创新中心与动物学湖南省高校重点实验室, 常德 415000;

3. Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO65211, USA

2. Collaborative Innovation Center for Efficient and Health Production of Fisheries in Hunan Province and Zoology Key Laboratory of Hunan Higher Education, Department of Life Science, Hunan University of Arts and Science, Changde 415000;

3. Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

铜绿微囊藻(Microcystis aeruginosa)存在于绝大多数淡水水域, 是水域生态系统中的重要成员, 但它在特定的环境条件下会成为优势藻, 进而种群暴发形成水华(Preston et al., 1980; Paerl et al., 2013).铜绿微囊藻水华的频繁暴发得益于微囊藻细胞在受到外界环境胁迫时能形成营养休眠体, 沉降至水域底泥表层, 采取“越冬”方式躲避环境恶劣期, 当外界环境条件适宜时微囊藻休眠体从底泥中启动复苏, 上浮迁移至上覆水体并再次暴发水华(Preston et al., 1980; Stone, 2011; Neilan et al., 2013).可以说, 底泥表层的铜绿微囊藻休眠体群是水华反复暴发的重要种源(Ståhl-Delbanco et al., 2003; Rossetti et al., 2010).因此, 要从源头控制铜绿微囊藻水华的暴发, 弄清楚这些种源在底泥表层的复苏机理至关重要.长期以来, 许多水环境科学工作者一直围绕铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的机理开展研究, 目前关于微囊藻休眠体复苏的生理生态学研究主要集中在营养盐(Ståhl-Delbanco et al., 2003; Schone et al., 2010)、温度(Cáceres et al., 1984; 谭啸等, 2009;Jähnichen et al., 2011)、光照强度(Brunberg et al., 2003)、底泥生物扰动及水动力(Tsujimura et al., 2000; Yamamoto, 2010)等领域, 很少有涉及底泥表层微生物因子对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏影响的研究, 对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的微生物菌群等因子研究更是鲜见.水域底泥表层环境极其复杂, 底泥菌群多样性丰富, 它们与微囊藻休眠体及环境一起构成一个复杂的浅层底泥生态系统, 那这些底泥菌是否对微囊藻休眠体复苏产生一定的作用和影响.本实验就此从频繁暴发微囊藻水华的湖南常德西洞庭白马湖水域筛选出的2株底泥优势菌(对白马湖进行了连续5年的水华跟踪研究, 从浅层底泥中筛选出118株底栖菌, 本实验所用的2株菌, 其中一株为蜡状芽孢杆菌(编号为Ba.sp06), 另一株为链霉球菌(编号为Str.v13), 2菌株比例具有显著的季节和年度变化), 与铜绿微囊藻休眠体室内共培养进行底泥模拟复苏实验, 以期从藻菌关系角度探讨底泥菌对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的影响及菌群动态变化.

2 材料与方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 底泥菌株2株底泥菌均来自西洞庭白马湖水域(2016年5月底暴发水华时从底泥中筛选并分离), 其中一株为蜡状芽孢杆菌, 编号为Ba.sp06, 另一株为链霉球菌, 编号为Str.v13, 2菌株均为该水域底栖优势菌.将2菌株分别进行活化后再进行扩大培养至菌浓度为1.2×108cfu·mL-1, 菌液备用.

2.2 铜绿微囊藻休眠体铜绿微囊藻(Microcystis aeruginosa, FACHB-434)与藻类培养液配方(BG11)均由中国科学院武汉水生生物研究所淡水藻种库提供.按照配方及培养方法对铜绿微囊藻进行扩大培养至稳定生长期, 利用血球计数板法与叶绿素(Chla)丙酮提取方法相结合对藻液浓度进行测定后, 往500 mL三角瓶中移入扩大培养并处于稳定生长期的M. aeruginosa 300 mL, 贴封口膜后于温度4 ℃、黑暗条件下静置3个月后倒去上层溶液, 浓缩制备成休眠体藻泥备用(Thomas et al., 1986).由于制备的藻泥中活细胞数(能够复苏的休眠体)占细胞总数的95%左右, 即有5%的藻细胞损耗, 因此, 在与底泥混合进行复苏实验时适当增加一定比例的藻泥或计算复苏率时去除5%的藻细胞损耗, 本实验制备的藻泥中能够复苏的休眠体浓度为1.4×1010 cell·mL-1.

2.3 实验用培养液与底泥实验过程中所用培养液为改良后的湖水, 湖水和底泥均取自西洞庭白马湖, 湖水用10 μm网孔径的钢筛进行过滤预处理(湖水理化性质见表 1), 底泥用网孔径125 μm的钢筛过滤预处理.为排除底泥与湖水(实验用培养液)中原生动植物及微生物对实验的影响, 对过滤后的湖水和底泥采取灭菌(121 ℃, 30 min)操作, 同时为充分满足菌群与铜绿微囊藻复苏过程中所需的营养, 在每1000 mL灭菌的湖水中分别加入20 mmol·L-1 NaNO3和4 mmol·L-1 K2HPO4各1 mL, 改良后的湖水和底泥(灭菌)备用.

| 表 1 西洞庭白马湖水体性质 Table 1 The properties of water body in Baima Lake of west Dongting |

取400 mL灭菌底泥与10 mL铜绿微囊藻休眠体藻泥混匀(混匀底泥含休眠体细胞总量为14×1010cells), 并均匀平铺于直径15 cm、高50 cm的特制圆柱形刻度玻璃筒中, 再用扩大培养的Ba.sp06与Str.v13两底泥细菌菌液浸润包埋底泥.底泥中所加入的两菌浓度比分别设为1:1(即各加菌液1 mL, 此时起始菌浓度均为1.5×105cfu·g-1(以鲜重计), 以1—3月2菌株各自在白马湖底泥中的平均菌浓度为参照)且设单菌平行实验组(各加菌液1 mL)、2:1(即加Ba.sp06菌液2 mL, 浓度为2×105cfu·g-1(以鲜重计);加Str.v13菌液1 mL, 浓度为1×105 cfu·g-1(以鲜重计))且设单菌平行实验组(一组加Ba.sp06菌液2 mL, 另一组加Str.v13菌液1 mL)、1:2(即加Ba.sp06菌液1 mL, 浓度为1×105cfu·g-1(以鲜重计);加Str.v13菌液2 mL, 浓度为2×105cfu·g-1(以鲜重计))且设单菌平行实验组(一组加Ba.sp06菌液1 mL, 另一组加Str.v13菌液2 mL)3个梯度, 对照组(CK)不加菌.实验设计的起始休眠体浓度、菌浓度及菌比均以冬季白马湖底泥表层微囊藻休眠体和各菌月平均浓度与动态为依据.然后, 用导流棒继续依玻璃筒壁缓慢(防止搅动底泥)加入培养液(改良湖水)至40 cm刻度处.再将玻璃筒置于温度10、15、20 ℃(3个梯度)、固定光照强度800 Lx(预实验表明, 与春末夏初季节白马湖水域湖底平均光强相当)、光:暗比为12 h:12 h的人工气候箱中静置培养24 d.所有实验全程3个平行组, 最终数据以平均值±标准差(X±SD)表示.

2.5 复苏藻细胞与底泥菌浓度检测 2.5.1 微囊藻休眠体复苏细胞检测每2 d定时(中午12:00)取样1次, 即用两端开口玻璃管(容量10 mL)插至玻璃筒底泥表层水体处, 封闭玻璃管上端开口, 垂直取出玻璃管, 混匀管内水样后, 超声波解聚处理(功率200 W, 时间2 min), 直接使用流式细胞仪(BD FACSAriaⅡ)进行检测, 计算并记录复苏藻细胞浓度(cells·mL-1).为防止前期复苏的藻细胞在水体中繁殖而影响复苏实验的准确性, 每次取水样后将玻璃筒中培养液全部移出, 再重新缓慢加入灭菌的改良培养液至40 cm刻度处继续培养, 第N天的复苏藻细胞浓度为第N天与第N天以前所有测得的藻细胞浓度之和(如培养8 d后的复苏藻细胞浓度为第8 d与第6 d、第4 d和第2 d测得的藻细胞浓度之和).通过处理组和对照组之间的对比分析, 判断不同温度和不同浓度比的底泥菌组合对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的影响及作用强度.

2.5.2 铜绿微囊藻休眠体特定复苏率为考察不同实验期铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的速率, 即单位时间内微囊藻休眠体复苏的数量动态, 采用特定复苏率(Specific Recruitment Rate, SRR)来表征;特定复苏率的计算参照公式μ=100×(lnB-lnA)/t进行, 其中μ表示特定复苏率(cells·mL-1d-1), B代表特定培养时间段尾的藻浓度(cells·mL-1), A代表特定培养时间段首的藻浓度(cells·mL-1), t代表特定培养时间段(d).

2.5.3 底泥菌浓度检测采用平板菌落计数法, 即每2 d定时(中午12:00)取1 g混匀底泥样品加入到9 mL无菌蒸馏水中进行梯度稀释, 以此方法稀释梯度10-1~10-7, 吸取稀释梯度10-5~10-7样品溶液各0.1 mL于FWA专用淡水细菌培养基平板涂布, 35 ℃生化培养箱中培养48 h后选择合适的梯度平板进行计数.由于底泥中只含有2菌种, 计数过程中采用形态学方法直接区分细菌并分别计算浓度(Bostrm et al., 1989).

2.6 数据分析数据作图采用Excel2007, 数据统计分析采用SPSS13.0软件, 试验期复苏藻细胞与细菌的动态变化情况采用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)及Duncans多重比较分析处理, 以p<0.05作为差异显著水平.

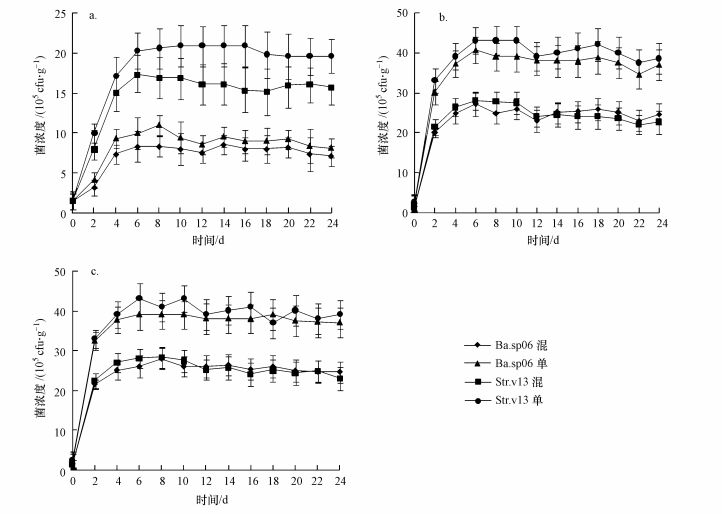

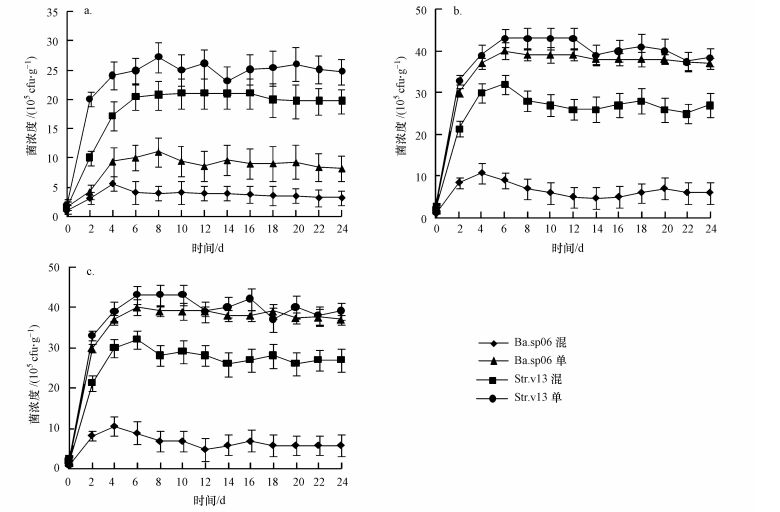

3 实验结果(Results) 3.1 不同起始菌比和温度条件下的菌动态Ba.sp06和Str.v13在较低温度(10 ℃)条件下的生长和繁殖速率差异显著(图 1a), 单菌组Str.v13显著强于Ba.sp06组.混合组起始菌比(Ba.sp06:Str.v13)为1:1时, 培养期间底泥中Ba.sp06最大菌浓度为8.56×105 cfu·g-1(以鲜重计, 下同)(第6 d), Str.v13最大菌浓度为17.3×105 cfu·g-1(第6 d), 说明在水域底泥温度较低情况下, Str.v13菌比Ba.sp06菌更容易成为底泥优势菌.起始菌比为1:2时, 低温(10 ℃)条件下两菌株在培养期间的菌浓度差异更显著(图 3a), Str.v13最大菌浓度为27.1×105 cfu·g-1 (第8 d), Ba.sp06最大菌浓度仅为5.58×105cfu·g-1(第4 d).两菌株起始浓度比为2:1时, 低温(10 ℃)条件下两菌株培养期间菌浓度无显著差异, 同时单菌组Ba.sp06(加菌液2 mL)与Str.v13(加菌液1 mL)在培养期间菌浓度也无显著差异(图 2a), 说明较高的起始Ba.sp06菌浓度弥补了低温不利条件对它的影响.10 ℃、各起始菌比条件下, 两菌株浓度基本上均在前6 d急剧上升到达最大值, 随后菌浓度趋稳并稍有下降(图 1a、图 2a、图 3a).

|

| 图 1 起始菌浓度比为1:1时的混合组与单菌组在不同实验温度条件下的菌浓度 (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃) Fig. 1 The density of bacteria under different temperature conditions when inoculum density ratio was 1:1 for Ba.sp06:Str.v13 or single bacteria group (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃) |

|

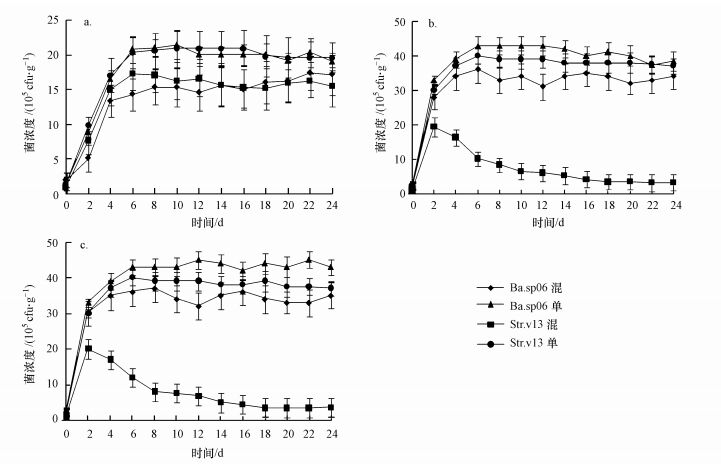

| 图 2 起始菌浓度比为2:1时的混合组与单菌组在不同实验温度条件下的菌浓度 (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃) Fig. 2 The density of bacteria under different temperature conditions when inoculum density ratio was 2:1 for Ba.sp06:Str.v13 or single bacteria group (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃) |

|

| 图 3 起始菌浓度比为1:2时的混合组与单菌组在不同实验温度条件下的菌浓度 (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃) Fig. 3 The density of bacteria under different temperature conditions when inoculum density ratio was 1:2 for Ba.sp06:Str.v13 or single bacteria group (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃) |

在较高温度(15~20 ℃)条件下, 混合组起始菌比为1:1时, 同一温度下Ba.sp06和Str.v13两菌株在培养期间菌浓度无显著差异(图 1b、图 1c).15 ℃时Ba.sp06菌与Str.v13菌最大浓度分别为27.1×105和28×105cfu·g-1(以鲜重计, 下同)(第6 d), 20 ℃时Ba.sp06菌与Str.v13菌最大浓度分别为27.9×105和28.3×105cfu·g-1(第6 d), 两不同温度(15与20 ℃)条件下Ba.sp06和Str.v13菌浓度也无显著性差异, 但显著高于10 ℃条件下的两菌浓度.15与20 ℃时, 两菌株浓度均在0~2 d急剧上升, 2~6 d菌浓度增速放缓并到达最大值, 后期菌浓度稍有下降(图 1b、图 1c).起始菌比为2:1时, 15和20 ℃条件下Ba.sp06菌浓度均显著高于Str.v13菌浓度, 两菌株浓度均在0~2 d急剧上升, 2~6 d Ba.sp06菌浓度缓速上升, 随后趋稳, 但Str.v13菌浓度开始持续下降.在15 ℃培养中后期(12~24 d), Ba.sp06菌浓度平均为33.4×105cfu·g-1, 而Str.v13菌浓度平均为3.26×105 cfu·g-1, 差异显著;在20 ℃培养中后期(12~24 d), Ba.sp06菌浓度平均为34.1×105 cfu·g-1, 而Str.v13菌浓度平均为3.32×105 cfu·g-1, 两者差异显著(图 2b、图 2c).起始菌比为1:2时, 两菌动态变化与起始菌比为2:1时正好相反, 15和20 ℃条件下Str.v13菌浓度均显著高于Ba.sp06菌浓度, 两菌株浓度均在0~4 d急剧上升, 4~6 d Str.v13菌浓度缓速上升, 随后趋稳下降, 但第4 d后Ba.sp06菌浓度开始持续下降.在15 ℃培养中后期(12~24 d), Ba.sp06菌浓度平均为6.24×105 cfu·g-1, 而Str.v13菌浓度平均为28.76×105 cfu·g-1, 差异显著; 在20 ℃培养中后期(12~24 d), Ba.sp06菌浓度平均为6.17×105 cfu·g-1, Str.v13菌浓度平均为28.3×105 cfu·g-1, 两者差异显著(图 3b、图 3c).对于单菌组, 在15与20 ℃条件下, 培养期间单菌组菌浓度均高于混合组, 且单菌组之间的菌浓度差异取决于起始菌浓度.

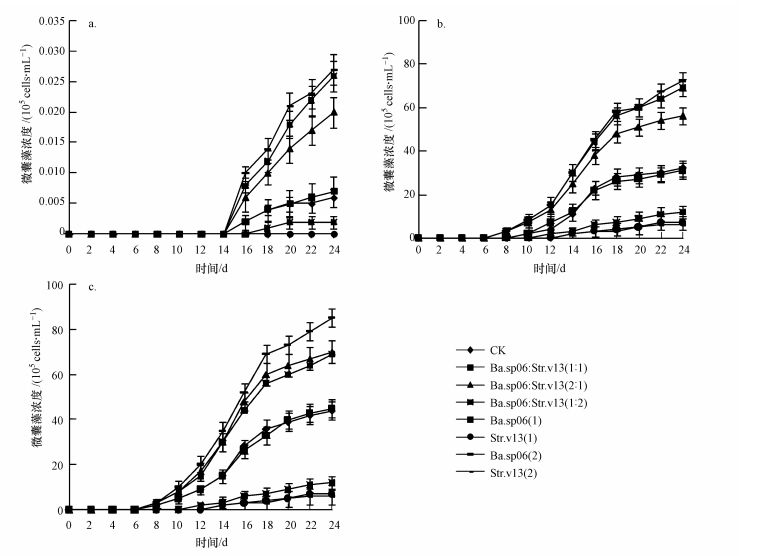

3.2 不同温度条件下的微囊藻休眠体复苏动态较低温(10 ℃)条件下, 无论是对照组、单菌组还是菌比为1:1、1:2或2:1的混合组, 底泥中的微囊藻休眠体复苏均不明显, 培养24 d上覆水体中铜绿微囊藻总浓度仅为0.003×105~0.03×105cells·mL-1(图 4a).同时, 在培养的第16 d可从水体中检测到复苏的微囊藻细胞.在较高温度(15 ℃)条件下, 起始菌比为1:1组与对照组(CK)的复苏趋势接近, 在第10 d水体中均检测到藻细胞, 培养24 d水体中藻细胞总浓度分别为31×105与30×105cells·mL-1, 实验全程两者无显著性差异, 但显著低于混合菌比2:1组和单菌Ba.sp06组(图 4b).起始菌比为2:1时, 在培养的第8 d检测到藻细胞, 随后水体藻浓度快速上升, 培养24 d水体中藻细胞总浓度达56×105 cells·mL-1, 显著高于菌比1:1组和对照组, 低于单菌Ba.sp06组.起始菌比1:2时, 在第12 d水体中检测到藻细胞, 水体中微囊藻浓度缓慢上升, 培养24d水体中藻细胞总浓度为12×105 cells·mL-1, 显著低于菌比2:1组、1:1组、对照组和单菌Ba.sp06组(图 4b).温度20 ℃条件下, 混合菌组、单菌组和对照组的复苏趋势与温度15 ℃条件下基本一致, 20 ℃条件下菌比1:2组的藻细胞浓度与15 ℃条件下菌比1:2组的藻细胞浓度无显著性, 菌比2:1组在两温度条件下也无显著性差异, 但菌比1:1组和对照组与15 ℃条件下的对应组藻细胞浓度具显著性差异(图 4b、图 4c).实验过程中, 对照组、单菌Ba.sp06组、菌比1:1和2:1组复苏的藻细胞浓度均显著高于菌比1:2组和单菌Str.v13组(图 4).

|

| 图 4 不同温度条件下复苏的微囊藻浓度 (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃;单菌组Ba.sp06(1)与Str.v13(1)表示加菌液1 mL, Ba.sp06(2)与Str.v13(2)表示加菌液2 mL) Fig. 4 Density of Microcystis cell in water under different temperature and inoculum ratio conditions (a.10 ℃, b.15 ℃, c.20 ℃; Ba.sp06 (1) indicated that 1 mL of the Ba.sp06 liquid was added in the single Ba.sp06 group, Ba.sp06 (2) indicated that 2 mL of the Ba.sp06 liquid was added in the single Ba.sp 06 group, the same to Str.v13 groups) |

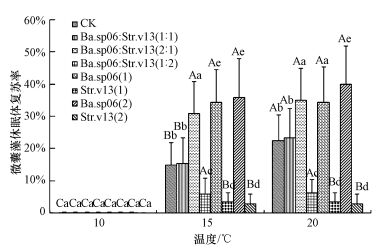

温度10 ℃条件下, 培养24 d各实验组底泥中的铜绿微囊藻休眠体均很少复苏进入水体, 从水体检测到的藻细胞总量表明休眠体复苏率仅为0.003%~0.03%(图 5).温度为15 ℃时, 起始菌比为2:1组的复苏率为31.0%, 显著高于菌比1:1组(复苏率15.5%)、1:2组(复苏率6.0%)和对照组(复苏率15.0%), 但稍低于单菌Ba.sp06组(含Ba.sp06(1)和Ba.sp06(2)), 菌比1:1组与对照组复苏率无显著性差异, 但菌比1:1组和对照组复苏率显著高于1:2组和单菌Str.v13组(图 5).温度为20 ℃时, 起始菌比为2:1组的复苏率为35%, 显著高于菌比1:1组(复苏率23.4%)、1:2组(复苏率6.5%)和对照组(复苏率22.6%), 稍低于单菌Ba.sp06组, 但与15 ℃时的2:1组复苏率无显著性差异.20 ℃条件下, 菌比1:1组与对照组复苏率无显著性差异, 菌比1:1组和对照组复苏率均显著高于1:2组和单菌Str.v13组, 同时均显著高于15 ℃条件下的菌比1:1组与对照组复苏率(图 5).在15 ℃条件下, 6~12 d培养期单菌Ba.sp06组特定复苏率显著高于其他组, 除菌比1:2组12~18 d培养期的特定复苏率与6~12 d培养期无显著性差异外, 各混合菌比组和对照组12~18 d培养期的特定复苏率均显著高于6~12 d和18~24 d两培养期, 但单菌Ba.sp06组12~18 d特定复苏率显著低于6~12 d.20 ℃时, 各菌组和对照组12~18 d培养期的特定复苏率也均显著高于6~12 d和18~24 d两培养期(表 2).15 ℃时, 6~12 d培养期菌比1:2组特定复苏率显著高于1:1组、2:1组和对照组, 其中, 单菌Str.v13组未检测到复苏藻细胞, 12~18 d培养期对照组的特定复苏率显著高于各菌比组, 18~24 d培养期菌比1:1组与2:1组的特定复苏率无显著性差异, 其他各组均具有显著性差异(表 2).20 ℃时, 6~12 d培养期菌比1:2组的特定复苏率显著低于1:1组、2:1组、对照组和单菌Ba.sp06组, 12~18 d培养期各组特定复苏率均无显著性差异(表 2).

|

| 图 5 实验24 d后不同温度条件下各组的复苏效果及其差异性 (不同大写字母代表同一菌组在不同温度条件下的微囊藻复苏率具显著性差异, 不同小写字母代表不同菌组在同一温度条件下的微囊藻复苏率具显著性差异) Fig. 5 Recruitment results and differences among allexperimental groups after 24 d culture |

| 表 2 不同培养期底泥中铜绿微囊藻休眠体的特定复苏率 Table 2 Specific recruitment rate of dormant Microcystis aeruginosa from sediment in differentculture period |

铜绿微囊藻种群暴发而形成水华得益于底泥表层铜绿微囊藻休眠体的复苏, 即底泥中的微囊藻休眠体是上覆水体中微囊藻细胞的主要种源(Preston et al., 1980; Yang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016).但底泥复苏的微囊藻休眠体占上覆水体中微囊藻细胞的比例一直存在争议, Brunberg等(2009)在对瑞典湖泊底泥越冬微囊藻复苏进行研究时发现, 底泥中微囊藻休眠体的30%~50%能进入水体参与水华的形成, 而Thomas等(1986)通过实验发现, 水华微囊藻中只有3.0%~4.2%来自底泥微囊藻的复苏;但Takamura等(1988)与Bostrom等(1989)甚至认为在富营养化水体中, 底泥微囊藻休眠体的数量会超过水体中的总微囊藻生物量最大值.水域底泥环境十分复杂, 影响底泥表层微囊藻休眠体复苏的因子众多(Sigee, 2005;Paerl et al., 2013;Ma et al., 2016), 可能正因不同水域环境的特异性而导致微囊藻休眠体复苏率的差异性.本实验模拟外界底泥环境开展试验, 主要考虑底泥中不同底泥菌的菌比与温度对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的影响, 实验结果表明, 不同混合菌比条件下的休眠体复苏率存在显著差异, 但各菌比组复苏率均低于单菌Ba.sp06组而高于单菌Str.v13组, 说明底泥菌Ba.sp06能促进休眠体复苏而Str.v13菌能抑制其复苏.特别在起始菌比为2:1组, 15 ℃培养24 d微囊藻休眠体复苏率为31%, 20 ℃时复苏率为35%(图 5), 这一结果与Brunberg等(2009)的实验结果接近;但菌比1:2组, 15 ℃时培养24 d微囊藻休眠体复苏率为6%, 20 ℃时复苏率为6.5%, 实验结果又与Thomas等(1986)相似.因此, 底泥铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏率及对水华的贡献要结合水域底泥环境因子综合探讨, 特别是底泥表层的菌群动态, 从本实验结果可以看出, 底泥菌群在微囊藻休眠体复苏过程中起着重要作用.另外, 对于浅水富营养化湖泊而言, 微囊藻休眠体的复苏与水深无关, 几乎可以发生在全湖范围.但在深水湖泊中, 铜绿微囊藻的复苏大部分都发生在浅水区域, 温跃层以下的藻类复苏对浮游带水华暴发的贡献几乎可以忽略(Hansson, 1996;苏玉萍等, 2012).本实验设计为40 cm的水深, 属于浅层水体底泥环境复苏模拟试验.

温度在铜绿微囊藻生活史中起着十分重要作用, 也是铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的重要因子之一(Preston et al., 1980;Karlsson et al., 2003; Ihle et al., 2005).有研究表明, 底泥中铜绿微囊藻休眠体能在5 ℃条件下存活, 并在9 ℃条件下开始复苏(Tsujimura et al., 2000; Yamamoto, 2009);又有研究表明, 当温度上升到7 ℃左右时, 铜绿微囊藻休眠体在湖泊底泥表面开始缓慢生长, 当温度上升到15 ℃时, 微囊藻群体开始复苏进入水体中(Thomas et al., 1986;Tsukada, 2006);李阔宇等(2004)也研究发现, 铜绿微囊藻在底泥中开始生长所需要的最低温度为10 ℃, 但这个温度并不能使其复苏进入水体; 陶益等(2005)以采自太湖底泥中的铜绿微囊藻为研究对象, 发现其进入水柱并开始生长的最适温度为18 ~20 ℃; 但随后有研究发现, 太湖泥样中的蓝藻复苏温度仅需12.5 ℃(谭啸等, 2009).本实验中无论是单菌组、混合菌组还是对照组, 在10 ℃条件下几乎未检测到复苏的藻细胞, 实验结果与李阔宇等(2004)和Tsukada(2006)的结果一致;同时在15 ℃和20 ℃时, 单菌组、混合菌组和对照组均检测到复苏的微囊藻细胞, 且起始菌比2:1组在两温度下的复苏率无显著性差异, 说明15 ~20 ℃是铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的最佳温度, 这一结果与陶益等(2005)的实验结果相吻合.

底泥表层是个复杂的生态系统, 底泥菌群与藻类植物是底泥的重要成员, 彼此相互影响和制约(Eiler et al., 2004).有研究表明, 一些菌群能促进藻类的生长(Ukeles et al., 1975;Spilling et al., 2008;Yang et al., 2015), 而有些菌群能抑制藻类的生长(Ddft et al., 1975;Dakhama et al., 1993;裴海燕等, 2005), 同时优势藻(特别是有毒微囊藻类)反过来影响底泥的菌群结构和空间分布(Deng et al., 2010; Neilan et al., 2013), 菌群彼此之间也互相影响(Lu et al., 2016).本实验所用菌株均从西洞庭白马湖水域底泥中筛选, Ba.sp06菌为促藻菌, 而Str.v13菌为抑藻菌, 两菌株在不同起始菌比和温度条件下的生长繁殖均先于铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏, 这在一定程度上利用了铜绿微囊藻复苏前的时间差(Lehman et al., 2010).在较低温度条件下(10 ℃), 菌株Str.v13的生长增殖能力比菌株Ba.sp06强(图 1a), 即使提升Ba.sp06菌浓度比(Ba.sp06: Str.v13 为2:1)培养24 d后, Ba.sp06菌浓度也未显著高于Str.v13菌浓度, 这说明低温条件不仅限制了铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的温度阈值, 同时底泥中的抑藻菌处于优势而进一步抑制其复苏, 这可能也是早春季节微囊藻水华很少暴发的原因之一.在较高温度(15与20 ℃)条件下, 两菌株的生长增殖速度受到起始菌比的影响, 菌比为2:1时, Ba.sp06菌浓度显著高于Str.v13菌浓度, 反之则相反, 表明高浓度菌株会抑制低浓度菌株的生长增殖(图 2、图 3), 进而影响铜绿微囊藻休眠体的复苏(图 4).有研究表明, 底泥菌群能改变底泥表层水体理化性质或分泌次代谢产物(如化感物质)影响其他菌群和藻类的生长(关英红等, 2008;Li et al., 2015; Borges et al., 2016).在本实验中, 两菌株对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的调控作用机理虽不清楚, 但对比实验发现, 底泥中促藻菌群占优势时, 能促进铜绿微囊藻休眠体的复苏, 抑藻菌占优势时会抑制其复苏(图 4).

复苏实验结果同时表明, 无论单菌组、对照组还是各混合菌组, 铜绿微囊藻特定复苏率(复苏速率)较快阶段均处于培养期的12~18 d, 该阶段的复苏速率显著高于培养初期(6~12 d)和后期(18~24 d)(表 2), 这说明微囊藻休眠体在复苏进入水体之前要经历一段“适应生长”蓄势期(Preston et al., 1980;Paterson et al., 2011;Li et al., 2014).15和20 ℃条件下各实验组整体复苏率处于6%~35%之间(图 5), 因本实验过程中不搅动底泥(防止底泥细菌和底泥胶体颗粒物质进入水体影响复苏微囊藻细胞检测), 可能包埋在底泥较深层的微囊藻休眠体无法复苏进入水体.有研究表明, 底泥生物扰动和水动力均能提升微囊藻休眠体的复苏率(Stahl-Delbanco et al., 2002; Yamamoto, 2010), 虽然底泥菌群的活动对底泥的搅动起一定作用, 但效果有限, 故室内底泥模拟实验复苏率与野外水域的实际复苏率存在一定差异.

本实验没有涉及底泥表层菌群对微囊藻休眠体复苏影响机制的探讨, 如底泥菌群是否通过改变底泥表层水体N:P比等理化性质, 是否通过分泌的代谢产物等化感物质影响微囊藻休眠体复苏, 底泥菌群是否会间接影响微囊藻休眠体的叶绿体光合作用能力及复苏基因的响应等, 这些都有待进一步的深入研究和探讨.

5 结论(Conclusions)1) 底泥菌株Ba.sp06与Str.v13对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏的作用效果取决于环境温度和两者的起始菌浓度比, 环境温度较低时(低于10 ℃), Str.v13菌的生长增殖能力强于Ba.sp06菌, 且该温度下铜绿微囊藻休眠体几乎不复苏;环境温度适宜(15~20 ℃)条件下, Ba.sp06与Str.v13菌浓度比为1:1时, 混合菌群对微囊藻休眠体复苏作用效果不显著(参比对照组);菌比为2:1时, Ba.sp06菌对Str.v13菌具有抑制作用, 培养过程中Ba.sp06菌浓度显著高于Str.v13菌, 混合菌显著促进微囊藻休眠体复苏;菌比为1:2时, Str.v13菌对Ba.sp06菌具有抑制作用, 培养过程中Str.v13菌浓度显著高于Ba.sp06菌, 混合菌显著抑制微囊藻休眠体复苏.

2) Ba.sp06与Str.v13菌株影响铜绿微囊藻休眠体的复苏率, 但未显著影响各复苏阶段的特定复苏率.无论单菌组、对照组还是各混合菌组, 铜绿微囊藻休眠体特定复苏率较快阶段均处于培养期的12~18 d, 该阶段的特定复苏率显著高于培养初期(6~12 d)和末期(18~24 d), 但同一阶段各实验组之间的特定生长率无显著性差异.

3) 由于Ba.sp06与Str.v13菌比变化对铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏率具有显著影响, 故可以在铜绿微囊藻休眠体复苏前期调节Ba.sp06与Str.v13菌比来控制其复苏率, 为从源头防控铜绿微囊藻水华的暴发提供理论依据.

Borges H, Wood S A, PuddickJ, et al. 2015. Intracellular, environmental and biotic interactions influence recruitment of benthic Microcystis (Cyanophyceae) in a shallow eutrophic lake[J]. Journal of Plankton Research, 38(5): 1289–1301.

|

Bostrm B, Pettersson A K, Ahlgren I. 1989. Seasonal dynamics of a cyanobacteria dominated microbial community in surface sediments of a shalloweutrophiclake[J]. Aquatic Sciences, 51: 153–178.

DOI:10.1007/BF00879300

|

Brunberg A K, Blomqvist P. 2003. Recruitment of Microcystis (Cyanophycae) from lake sediments:The importance of littoral inocula[J]. Journal of Phycology, 39(1): 58–63.

DOI:10.1111/jpy.2003.39.issue-1

|

Brunberg A K, Lyra C, Sivonen K, et al. 2009. High diversity of cultivable heterotropic bacteria in association with cyanobacterial water blooms[J]. The ISME Journal, 3: 314–325.

DOI:10.1038/ismej.2008.110

|

Cáceres O, Reynolds C S. 1984. Some effects of artificially enhanced anoxia on the Microcystis aeruginosa Kützemend Elenkin with special reference to the initiation of its annual growth cycle in lake[J]. Archivfur Hydrobiologia, 99: 379–397.

|

Dakhama A, Noue J D, Lavoie M C. 1993. Methods for the examination of organism diversity in soils[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 5(9): 297–306.

|

Ddft M, Sterwart W D R. 1975. Ecological studies on algal-lysing baeteria in fresh water[J]. Freshwater Biology, 5(1): 577–596.

|

Deng D G, Zhang S, Li Y Y, et al. 2010. Effects of Microcystis aeruginosa on population dynamics and sexual reproduction in two Daphniaspecies[J]. Journal of Plankton Research, 32: 1385–1392.

DOI:10.1093/plankt/fbq069

|

Ehlers B K. 2011. Soil microorganisms alleviate the allelochemical effects of a thyme monoterpene on the performance of an associated grass species[J]. PLoS One, 6: e26321.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0026321

|

关英红, 马军, 雷国元, 等. 2008. 一株溶藻菌株的分离鉴定及溶藻特性[J]. 环境科学学报, 2008, 28(7): 1288–1293.

|

李阔宇, 宋立荣, 万能. 2004. 底泥中微囊藻复苏和生长特性的研究[J]. 水生生物学报, 2004, 28(2): 113–118.

|

Hansson L A. 1996. Algal recruitment from lake sediments in relation to grazing, sinking, and dominance patterns in the phytoplankton community[J]. Limnologyand Oceanography, 41(6): 1312–1323.

DOI:10.4319/lo.1996.41.6.1312

|

Ihle T, Jahnichen S, Benndorf J. 2005. Wax and wane of Microcystis (cyanophyceae) and microcystins in lake sediment:a case syudy in Quitzdorf Reservoir (Germany)[J]. Journal of Phycology, 41: 479–488.

DOI:10.1111/(ISSN)1529-8817

|

Jähnichen S, Long B M, Petzoldt T. 2011. Microcystin production by Microcystis aeruginosa:Direct regulation by multiple environmental factors[J]. Harmful Algae, 12: 95–104.

DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2011.09.002

|

Karlsson-Elfgren I, Rydin E, Hyenstrand P, et al. 2003. Recruitment and pelagic growth of Gloeotrichia echinulate(cyanophyceae) in Lake Erken[J]. Journal of Phycology, 39: 1050–1056.

DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.2003.03-030.x

|

Lehman P W, Teh S J, Boyer G L, et al. 2010. Initial impacts of Microcystis aeruginosa blooms on the aquatic food web in the San Francisco Estuary[J]. Hydrobiologia, 637: 229–248.

DOI:10.1007/s10750-009-9999-y

|

Li K Y, Song L R. 2014. Studies of recruitment and growth characteristic of Microcystis in sediment[J]. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 28(2): 118–122.

|

Li M, Xiao M. 2016. Environmental factors related to the dominance of Microcystis wesenbergii and Microcystis aeruginosain an eutrophic lake[J]. Environmental Earth Science, 75: 1866–1874.

|

Lu Y P, Wang J, Zhang X Q, et al. 2016. Inhibition of the growth of cyanobacteria during the recruitment stage in Lake Taihu[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23: 5830–5838.

DOI:10.1007/s11356-015-5821-8

|

Ma J R, Qin B Q, Paerl H W, et al. 2016. The persistence of cyanobacterial (Microcystis spp.) blooms throughout winter in Lake Taihu, China. Limnology and Oceanography[M]. : 711–722.

|

Neilan B A, Pearson L A, Muenchhoff J, et al. 2013. Environmental conditions that influence toxin biosynthesis in cyanobacteria[J]. Environment Microbiology, 15: 1239–1253.

DOI:10.1111/emi.2013.15.issue-5

|

Paerl H W, Otten T G. 2013. Blooms bite the hand that feeds them[J]. Science, 342: 433–434.

DOI:10.1126/science.1245276

|

Paterson M, Schindler D, Hecky R, et al. 2011. Comment:Lake 227 shows clearly that controlling inputs of nitrogen will not reduce or prevent eutrophication of lakes[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 56: 1545–1547.

DOI:10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1545

|

Preston T, Stewart W D P, Reynolds C S. 1980. Bloom-forming cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa overwinters on sediment surface[J]. Nature, 288: 365–370.

DOI:10.1038/288365a0

|

裴海燕, 胡文容, 曲音波, 等. 2005. 一株溶藻细菌的分离鉴定及其溶藻特性[J]. 环境科学学报, 2005, 25(6): 796–802.

|

Rossetti V, Schirrmeister B E, Bernasconi M V. 2010. The evolutionary path to terminal differentiation and division of labor in cyanobacteria[J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 262(1): 23–34.

DOI:10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.09.009

|

Schone K, Jähnichen S, Ihle T, et al. 2010. Arriving in better shape:Benthic Microcystis as inoculum for pelagic growth[J]. Harmful Algae, 9(5): 494–503.

DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2010.03.005

|

Sigee D.2005.Freshwater Microbiology.Biodiversity and Dynamic Interactions of Microorganisms in the Aquatic Environment[M].Chichester, UK:John Wildey and Sons.328-338

|

Spilling K, Markager S. 2008. Ecophysiological growth character-istics and modeling of the onset of the spring bloom in the Baltic Sea[J]. Journal of Marine Systems, 73: 323–337.

DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2006.10.012

|

Ståhl-Delbanco A, Hansson L A, Gyllström M. 2003. Recruitment of resting stages may induce blooms of Microcystisat low N:P ratios[J]. Journal of Plankton Research, 25(9): 1099–1106.

DOI:10.1093/plankt/25.9.1099

|

Stahl-Delbanco A, Hansson L A. 2002. Effects of bioturbation on recruitment og algal cells from the "seed bank"of lake sediment[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 47: 1836–1843.

DOI:10.4319/lo.2002.47.6.1836

|

Stone R. 2011. China aims to turn tide against toxic lake pollution[J]. Science, 333: 1210–1211.

DOI:10.1126/science.333.6047.1210

|

苏玉萍, 李艳芳, 钟厚璋, 等. 2012. 山仔水库沉积物蓝藻复苏试验研究[J]. 环境科学学报, 2012, 32(2): 341–348.

|

谭啸, 孔繁翔, 于洋, 等. 2009. 升温过程对藻类复苏和群落演替的影响[J]. 中国环境科学, 2009, 29(6): 578–582.

|

陶益, 孔繁翔, 曹焕生, 等. 2005. 太湖底泥水华蓝藻复苏的模拟[J]. 湖泊科学, 2005, 17(3): 231–236.

|

Takamura N, Yasuno M. 1988. Sedimentation of phytoplankton populations dominated by Microcystis in a shallow lake[J]. Journal of Plankton Research, 10: 283–299.

DOI:10.1093/plankt/10.2.283

|

Thomas R H, Walsby A E. 1986. The effects of temperatures on recovery of buoyancy by Microcystis[J]. Journal of General Microbiology, 132(6): 1665–1672.

|

Tsujimura S, Tsukada H, Nakahara H, et al. 2000. Seasonal variations of Microcystis populations in sediments of lake Biwa Japan[J]. Hydrobiologia, 434(1-3): 183–192.

|

Tsukada H.2006.A study on the life history and the factor affecting the dominance of Microcystis in eutrophic lakes[D].Kyoto:Kyoto University

|

Ukeles R, Bishop J. 1975. Enhancement of phytoplankton growth by marine bacteria[J]. Journal of Phycology, 11: 142–149.

|

Wang W J, Shen H, Shi P L, et al. 2016. Experimental evidence for the role of heterotrophic bacteria in the formation of Microcystis colonies[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 28(2): 82–394.

|

Yamamoto Y. 2010. Contribution of bioturbation by the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkia to the recruitment of bloom-forming cyanobacteria from sediment[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 69(1): 102–111.

|

Yang C Y, Yi L, Zhou Y Y, et al. 2015. Illumina sequencing-based analysis of free-living bacterial community dynamics during an akashiwo sanguine bloom in Xiamen sea, China[J]. Scientific Reports, 5: 8476–8486.

DOI:10.1038/srep08476

|

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37