2. 清华大学环境学院, 新兴有机污染物控制北京市重点实验室, 北京 100084

2. Beijing Key Laboratory for Emerging Organic Contaminants Control, School of Environment, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084

YU Gang, E-mail:yg-den@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn

随着高分子材料工业的发展,塑料、橡胶、纤维等合成材料得到广泛应用,而阻燃剂作为合成材料的重要助剂,其主要作用是使合成材料具有自熄性和难燃性,目前已在纺织品、聚氯乙烯、泡沫、棉花、橡胶、树脂等材料的制造工艺中被普遍使用(Reemtsma et al., 2008;Marklund et al., 2005),进而广泛用于室内装潢、家具、建材和各类电器中.2013年全球阻燃剂总消费量约为195万t,其中,磷代阻燃剂(Phosphorus Flame Retardants, PFRs)在各类阻燃剂中占有重要地位,占总使用量的19%(张月,2014).据统计,2006年欧洲的阻燃剂总使用量约为46.5万t,其中,PFRs占20%之多(11%含卤,9%无卤)(Bourbigot et al., 2007).大部分PFRs属于添加型阻燃剂,所以很容易释放到环境中,普遍存在于室内灰尘、空气、饮用水、沉积物、甚至生物体中(van der Veen et al., 2012).

由于挥发性较弱,PFRs易与其他形貌、尺寸各不相同的灰尘颗粒结合在一起在室内外环境中广泛存在,人们主要通过呼吸、摄食、皮肤接触等途径对灰尘及其中蕴含的PFRs产生暴露(Butte et al., 2002;段海静等,2015;Frederiksen et al., 2009;Praveena et al., 2015).

20世纪90年代以来,大量研究证明了室内外灰尘是威胁人体健康的重要因素(Weschler et al., 2008).灰尘中PFRs的污染及人体暴露近年来正日益成为环境化学领域的研究热点,然而我国在这方面的研究尚不多见.同时,有研究指出灰尘的粒径组成会对分析结果产生一定影响(Wensing et al., 2005);主要有以下两方面原因:① 不同粒径的灰尘中污染物的含量可能存在很大差异(Butte et al., 2002;Lewis et al., 1999); ② 灰尘粒径是其是否能产生人体暴露的主要影响因素(Mercier et al., 2011).然而,目前关于灰尘中PFRs粒径分布特征的认识还比较有限.此外,由于多溴联苯醚(Poly Brominated Diphenyl Ethers, PBDEs)的禁用,PFRs产量及使用量近年来已明显增加,将可能产生更明显的潜在健康威胁.因此,展开PFRs在灰尘中粒径分布规律及人体暴露的研究,将有助于增进对中国有机阻燃剂污染特征及人体暴露水平的认识.

本文采用气相色谱-质谱联用技术,对北京市5类典型室内外灰尘中3种PFRs(TBOEP、TCEP、TCIPP)进行定量检测,从污染特征、粒径分布规律及人体暴露水平3个方面探究PFRs在室内外灰尘中的污染及人体暴露特征.这将有助于增进对PFRs在我国不同类型灰尘中的赋存分配规律、影响因素及潜在人体健康影响的认识,为PFRs的应用管理提供科学依据.

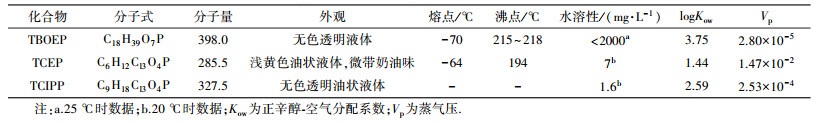

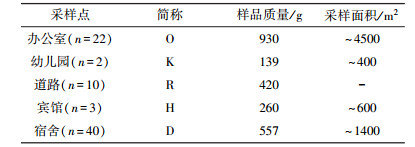

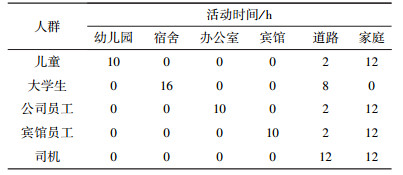

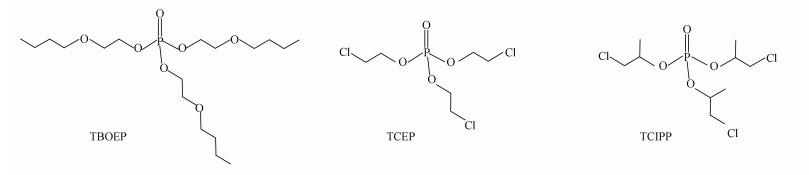

2 材料与方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 样品选取为了解北京市典型室内外地面灰尘中3种PFRs(三(2-丁氧乙基)磷酸酯(TBOEP)、磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯(TCEP)、磷酸三(2-氯异丙基)酯(TCIPP),结构式见图 1,物理化学性质见表 1(李俊,2014))的污染特征,以室内陈设具有典型代表性的办公室、幼儿园、宾馆、大学生宿舍作为室内研究对象,道路作为室外研究对象,分析室内外灰尘中PFRs的污染特征及人体暴露水平.于2012年10月分别选取了22间办公室、2所幼儿园、3座宾馆、40间大学生宿舍及位于北京市三环线上的10个采样点,分别用吸尘器、鬃刷采集室内外地面灰尘样品(采样信息见表 2).其中,办公室、幼儿园、宾馆地面铺有地毯,大学宿舍为水泥地面.采样期间的气象信息如下:平均降水量为23.9 mm,平均湿度为58%,平均气压为1016.3 hPa,平均气温为13.9 ℃.采样过程中每一个采样点均处于正常运转状态.对于宿舍和幼儿园,由研究人员前往采样点用除尘器对室内地面进行全面除尘,采样速率约为2 m2· min-1,记录采样量与采样面积;对于宾馆和办公室,先由负责卫生的工作人员或房间主人用除尘器对房间地面进行清洁,之后研究人员从除尘器中采集灰尘样品;在道路灰尘样品采集过程中,首先确定了位于北京市三环线上的10个采样点,委托北京环境卫生设计科学研究所工作人员采集道路地面灰尘样品.采样完毕后,将用铝箔包裹的除尘袋、灰尘样品放入自封袋中,带回实验室置于-20 ℃冰箱冷藏保存.将采集自同一类型环境的灰尘样品混合在一起,过2 mm筛子,得到5个粒径 < 2 mm的混合样品.通过不锈钢筛对每类混合样品进行进一步的粒径分级,每类灰尘获得9个不同粒径级的样品:F1(900~2000 μm)、F2(500~900 μm)、F3(400~500 μm)、F4(300~400 μm)、F5(200~300 μm)、F6(100~200 μm)、F7(74~100 μm)、F8(50~74 μm)和F9( < 50 μm),共计45个样品供分析.

|

| 图 1 3种PFRs的结构式 Fig. 1 Structural formula of three kinds of PFRs |

| 表 1 3种PFRs的物理化学性质 Table 1 Physical and chemical properties of three kinds of PFRs |

| 表 2 灰尘样品的采样信息 Table 2 Sampling information of dust samples |

仪器:气相色谱(Agilent 6890)-质谱(Agilent 5973) 仪、超声波萃取仪(Branson 5510)、氮吹仪(Organomation 5085)、十万分之一天平(Sartorius CPA225D)、马弗炉(Thermo BF51766KC-1).试剂:丙酮(色谱纯)、正己烷、异辛烷、乙酸乙酯、3种PFRs标样、内标TBOEP-d6、TCEP-d12.所有玻璃仪器在使用前经充分清洗后放在马弗炉中焙烧3 h(温度设为450 ℃).

2.3 样品前处理用天平准确称量40 mg的灰尘样品和25 mg的标准土壤样品(SRM2585) 并记录样品质量,将准确称量的样品放入玻璃离心管(12 mL),加入已知质量的内标(TBOEP-d6、TCEP-d12);在离心管中加入2.5 mL正己烷/丙酮(体积比3/1) 涡旋1 min,之后超声萃取10 min(温度设定在38 ℃)并收集上清液;3次萃取之后,将上清液集中到一支离心管中,用氮气吹至近干,然后再加入1 mL正己烷使之溶解.分别用8 mL乙酸乙酯和6 mL正己烷淋洗SPE(500 mg,3 mL)小柱进行活化处理,再将溶解后的萃取液转移到SPE小柱中;先用10 mL正己烷淋洗小柱,再用8 mL乙酸乙酯淋洗小柱并收集淋洗液;将淋洗液用氮吹浓缩至近干,加入100 μL异辛烷/乙酸乙酯(体积比1/1),涡旋1 min后转至透明色谱瓶中;将色谱瓶放置在冰箱中(-4 ℃)冷藏12 h,去除沉淀物并将上清液移至新的色谱瓶内以备仪器分析(Van den Eede et al., 2012).

2.4 仪器分析采用气相色谱-质谱联用仪(GC-MS),使用电子电离源(EI)在SIM模式下,不分流进样1 μL检测PFRs.GC-MS分析条件如下:色谱柱为RTI5MS(30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm);以高纯He为载气,流量设定为1 mL· min-1;进样口温度为280 ℃,离子源温度为200 ℃,接口温度为280 ℃.升温程序设置为:① 50 ℃保持1 min,再以15 ℃· min-1升至200 ℃;② 200 ℃保持1 min,再以4 ℃· min-1升至250 ℃;③ 以20 ℃· min-1升至300 ℃;④ 300 ℃保持4 min.3种PFRs的定量离子、参考离子(m/z)分别为:TCEP:249/63、143、251;TCIPP:125/99、201、277、157;TBOEP:85/100、199、299.

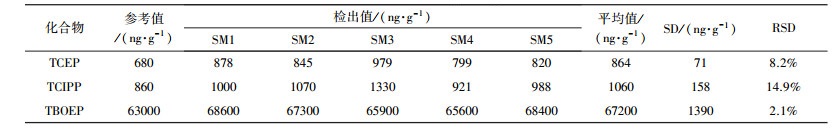

2.5 质量控制所有45个灰尘样品分为5批进行前处理,每批实验设3个空白和1个标准土样,共15个空白和5个标准土样.对操作空白的分析结果显示,TBOEP、TCEP、TCIPP基本都没有被检出.在统计分析数据前,计算了所有空白样品中有机阻燃剂含量的平均值,并对每一个目标灰尘样品的数据做扣除空白处理.对标准土样的分析结果显示(表 3),5个SRM2585样品的分析数据具有良好的重复性和准确性,能够与文献报道(Van den Eede et al., 2012)的验证值相吻合.

| 表 3 目标化合物在SRM2585中的检出值 Table 3 Detected concentration of target compounds in SRM2585 |

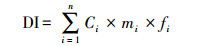

地面降尘中的污染物主要通过皮肤接触和灰尘摄食被人体暴露,而公认的最主要的暴露途径则是灰尘摄食.现采用如下模型(Frederiksen et al., 2009)计算对大学生、儿童、办公室员工、宾馆员工及司机5类人群对PFRs的暴露情况:

|

式中,DI为PFRs暴露量(ng· d-1);Ci为PFRs在环境i中的含量(ng· g-1);fi为人们在环境i中的活动时间与1 d总时间的比例;m为灰尘的日摄入量(g· d-1).本方法采用USEPA的人体灰尘日摄入量参数,成人和儿童对灰尘的日摄入量分别为50 mg· d-1和200 mg· d-1.

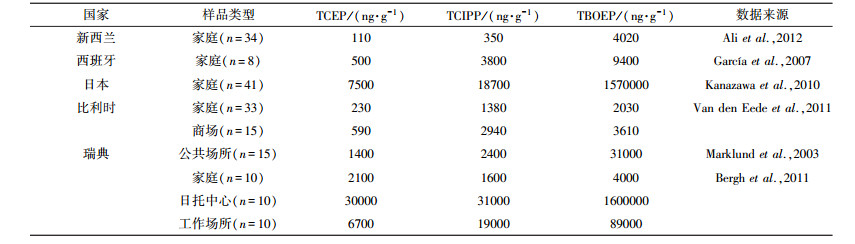

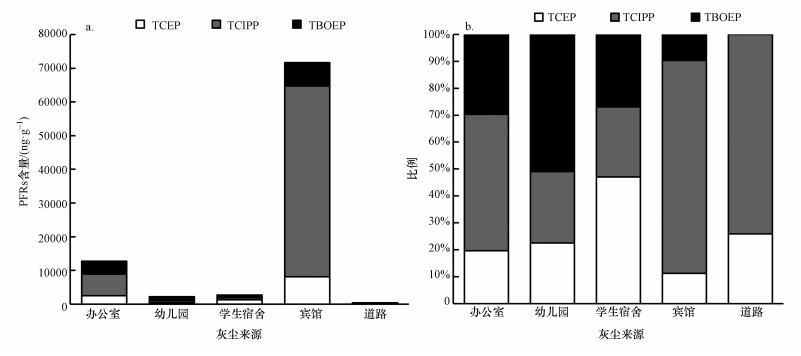

3 结果与讨论(Results and discussion) 3.1 PFRs在室内外灰尘中的含量及组分特征由于人体对灰尘中细颗粒物的暴露几率更高(Cao et al., 2012;丁锦建,2016),本文选择具有代表性的F9( < 50 μm)样品探讨PFRs在不同类型灰尘中污染特征的差异.总体上,5类灰尘中PFRs的含量排序为:宾馆>办公室>宿舍>幼儿园>道路(图 2a).宾馆灰尘中PFRs的含量之所以最高,可能是因为PFRs广泛应用在纺织品、泡沫及地毯中,而这些材料在宾馆中的使用量都远超其它室内环境;办公室和宿舍灰尘中PFRs的含量次之,可能是因为办公室和宿舍内使用大量电子产品,且宿舍环境中存在较多的纺织品.表 4显示了文献报道的不同国家室内灰尘中PFRs的污染状况(Ali et al., 2012;García et al., 2007;Kanazawa et al., 2010;Van den Eede et al., 2011;Marklund et al., 2003;Bergh et al., 2011),由此可见,灰尘中PFRs的含量在不同国家和不同环境中存在较大差异,而本文检出值介于各国数据之间,处于中上等程度的污染水平.

|

| 图 2 各灰尘样品中目标PFRs的空间含量变化(a)及结构分布(b) Fig. 2 Levels(a) and patterns(b) of PFRs in five types of dust samples |

| 表 4 文献报道的各国室内灰尘中PFRs中值含量 Table 4 PFRs median concentration in indoor dust from various countries in the literature |

具体来讲,3种PFRs中,TCIPP在宾馆灰尘中的含量最高(56700 ng· g-1),是幼儿园灰尘中的近100倍(572 ng· g-1);同样,TCEP在宾馆灰尘中的含量(8070 ng· g-1)也是最高,办公室灰尘(2500 ng· g-1)和宿舍灰尘(1240 ng· g-1)次之,幼儿园灰尘中最低(486 ng· g-1);TBOEP在宾馆灰尘中含量最高(6960 ng· g-1),办公室灰尘(3790 ng· g-1)和宿舍灰尘(1100 ng· g-1)次之,幼儿园灰尘最低(715 ng· g-1).对室外环境道路来说,TCIPP和TCEP都表现出比较低的含量,TBOEP没有检出.

与文献报道数据相比较可见(表 4),办公室灰尘中和幼儿园灰尘中3种PFRs含量均低于瑞典工作场所和日托中心的数据.学生宿舍和家庭的功能和构造类似,具有可比较性,宿舍灰尘中TCEP含量(1240 ng· g-1)高于新西兰、西班牙和比利时家庭的数据(分别为110、500、230 ng· g-1),低于日本和瑞典家庭的数据(分别为7500、2100 ng· g-1);TCIPP含量(690 ng· g-1)高于新西兰家庭的数据(350 ng· g-1),低于西班牙、日本、比利时和瑞典家庭的数据(分别为3800、18700、1380、1600 ng· g-1);TBOEP含量均低于文献报道各国家庭的数据.

图 2b展示了3类PFRs在5类灰尘样品中的详细组成结构.TCIPP在道路、宾馆和办公室灰尘样品中所占的比例最高(分别为74%、79%、50.7%);幼儿园灰尘中TBOEP所占比例最高(51%);学生宿舍灰尘中TCEP所占比例最高(47%).TCEP、TCIPP和TBOEP在5类灰尘样品中呈现出不同的组分结构特征,反映了不同环境中3种PFRs的应用结构存在明显差异.

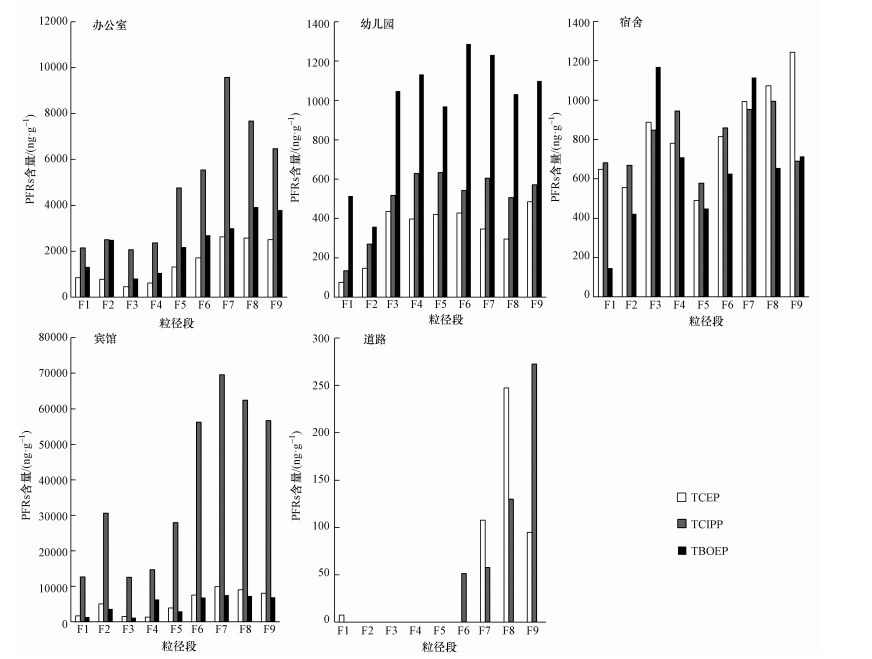

3.2 PFRs在室内外灰尘中的粒径分布规律及影响因素分析灰尘是许多有机污染物的储藏库,并且室内灰尘有复杂的自然、人为来源,其粒径至少跨越从nm到mm 4个数量级.有文献指出(Ruby et al., 2012),污染物在灰尘中的粒径分布特征与污染物的来源和排放方式、污染物的物理化学性质及采样点的气象条件等因素有关,也有相关研究发现(Cao et al., 2012),灰尘粒径可能是影响污染物在灰尘中分布的一个重要因素,因而评估人体对灰尘中污染物的暴露时需考虑粒径因素.

5类灰尘样品中3种PFRs在不同径级颗粒物中的粒径分布结果如图 3所示.细颗粒物有更大的比表面积,据此有学者认为灰尘中有机污染物的含量就会随粒径的减小而升高(Mercier et al., 2011;Van den Eede et al., 2012).但经研究发现,PFRs在灰尘中的含量也可能不随粒径减小而升高.在4类室内灰尘中,3种PFRs大都呈现2个峰值,分别在F3和F7附近(图 3).在学生宿舍灰尘中,TBOEP、TCEP、TCIPP的2个峰值几乎相等;而在其他室内环境中,3种PFRs在F7附近的峰值都比在F3附近的峰值要高,表明这些物质更多的富集在细小的颗粒灰尘中.幼儿园灰尘中PFRs在F3~F9范围的分布相对均匀且无明显峰值.道路灰尘中F8和F9中TCEP和TCIPP呈现出了明显的峰值,呈现出与室内灰尘显著不同的粒径分布特征.有研究已经证明了材料磨损在阻燃剂释放的过程中起重要作用(Suzuki et al., 2009;Webster et al., 2009),本实验在F2附近粒径段发现了较高含量的PFRs,进而证明了在粗颗粒灰尘中可能有毫米尺寸的添加了PFRs的磨损纤维或颗粒;也间接说明不同来源的灰尘颗粒具有不同的粒径特征.此外,PFRs在办公室、宾馆和道路灰尘中在细颗粒物上的富集则反映了在这些环境中PFRs通过挥发的途径释放到环境中,进而被粒径较小的灰尘颗粒吸收则是这3类灰尘中PFRs的主导型性释放机制(Cao et al., 2013;Mercier et al., 2011).

|

| 图 3 3种PFRs在各类环境中的粒径分布 Fig. 3 Particle size distribution of three kinds of PFRs in five types of dust |

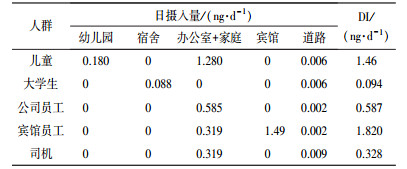

有研究指出,人摄入灰尘后,对细颗粒中所蕴含污染物的吸收率更高(Lewis et al., 1999),因此,采用粒径段F9( < 50 μm)的相关数据进行了PFRs的人体暴露评估.因进入家庭中采样有诸多不便,本次实验未能获得家庭灰尘样品以供研究之用,有研究报道, 家庭灰尘中PFRs的污染水平与办公室的接近(Besis et al., 2012),因此,根据获得的办公室灰尘样品中的相关数据,近似估计了家庭灰尘中PFRs的含量.基于5类人群的生活习惯,对不同人群的活动时间进行出合理的分配(表 5),进而计算了5类人群在不同环境中3种PFRs的摄入量(表 6).

| 表 5 不同人群在不同场所活动的时间 Table 5 Time of activities in different places for different populations |

| 表 6 不同人群3种PFRs总的日摄入量 Table 6 Total daily intake of three kinds of PFRs |

研究发现,宾馆员工对3种PFRs的总日均暴露量最高(1.820 ng· d-1),其次是儿童(1.460 ng· d-1),而大学生(0.094 ng· d-1)的总日均暴露量最低;宾馆员工对PFRs的日暴露量是大学生的近20倍;儿童一天中在家的摄入量最高,是宾馆员工和司机的近4倍;5类人群在道路上的摄入量相对都比较低.这说明因宾馆中PFRs的含量极高,使得宾馆员工对3种PFRs的暴露水平明显高于其他人群;由于儿童的日摄入灰尘量远远大于成人,因而儿童的暴露水平在不同人群中处于较高水平,需要引起重视.

4 结论(Conclusions)北京市室内外灰尘中3种目标PFRs在宾馆环境中的污染水平均为最高;室内灰尘中PFRs的积累明显高于室外道路灰尘.室内外环境灰尘中的3种目标PFRs的粒径分布规律差异显著;PFRs的来源及环境因素都会对灰尘中PFRs的粒径分布产生一定影响.宾馆员工及儿童对3种目标PFRs的暴露水平较高,需引起重视.

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Ali N, Dirtu A C, Van den Eede N, et al. 2012. Occurrence of alternative flame retardants in indoor dust from New Zealand:Indoor sources and human exposure assessment[J]. Chemosphere, 88(11): 1276–1282. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.100 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Bergh C, Torgrip R, Emenius G, et al. 2011. Organophosphate and phthalate esters in air and settled dust-a multi-location indoor study[J]. Indoor Air, 21(1): 67–76. DOI:10.1111/ina.2010.21.issue-1 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Besis A, Samara C. 2012. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in the indoor and outdoor environments-A review on occurrence and human exposure[J]. Environmental Pollution, 169: 217–229. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2012.04.009 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Bourbigot S, Duquesne S. 2007. Fire retardant polymers:recent developments and opportunities[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 17(22): 2283–2300. DOI:10.1039/b702511d |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Butte W, Heinzow B. 2002. Pollutants in house dust as indicators of indoor contamination[J]. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 175: 1–46. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Cao Z G, Yu G, Chen Y S, et al. 2012. Particle size:A missing factor in risk assessment of human exposure to toxic chemicals in settled indoor dust[J]. Environment International, 49: 24–30. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2012.08.010 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Cao Z G, Yu G, Chen Y S, et al. 2013. Mechanisms influencing the BFR distribution patterns in office dust and implications for estimating human exposure[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 252: 11–18. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | 丁锦建. 2016. 典型有机磷阻燃剂人体暴露途径与蓄积特征研究[D]. 杭州: 浙江大学 http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10335-1016118136.htm |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | 段海静, 蔡晓强, 阮心玲, 等. 2015. 开封市公园地表灰尘重金属污染及健康风险[J]. 环境科学, 2015, 36(8): 2972–2980. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Frederiksen M, Vorkamp K, Thomsen M, et al. 2009. Human internal and external exposure to PBDEs-A review of levels and sources[J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 212(2): 109–134. DOI:10.1016/j.ijheh.2008.04.005 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | García M, Rodríguez I, Cela R. 2007. Microwave-assisted extraction of organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers from indoor dust samples[J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 1152(1/2): 280–286. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Kanazawa A, Saito I, Araki A, et al. 2010. Association between indoor exposure to semi-volatile organic compounds and building-related symptoms among the occupants of residential dwellings[J]. Indoor Air, 20(1): 72–84. DOI:10.1111/ina.2009.20.issue-1 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Lewis R G, Fortune C R, Willis R D, et al. 1999. Distribution of pesticides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in house dust as a function of particle size[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 107(9): 721–726. DOI:10.1289/ehp.99107721 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | 李俊. 2014. 有机磷酸酯阻燃剂在饮用水及大气中的分布特征及健康风险评价[D]. 南京: 南京大学 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Marklund A, Andersson B, Haglund P. 2003. Screening of organophosphorus compounds and their distribution in various indoor environments[J]. Chemosphere, 53(9): 1137–1146. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00666-0 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Marklund A, Andersson B, Haglund P. 2005. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in air from various indoor environments[J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 7(8): 814–819. DOI:10.1039/b505587c |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Mercier F, Glorennec P, Thomas O, et al. 2011. Organic contamination of settled house dust, a review for exposure assessment purposes[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(16): 6716–6727. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Reemtsma T, Quintana J B, Rodil R, et al. 2008. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in water and air Ⅰ.Occurrence and fate[J]. Trac-Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 27(9): 727–737. DOI:10.1016/j.trac.2008.07.002 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Praveena S M, Mutalib N S A, Aris A Z. 2015. Determination of heavy metals in indoor dust from primary school (Sri Serdang, Malaysia):Estimation of the health risks[J]. Environmental Forensics, 16(3): 257–263. DOI:10.1080/15275922.2015.1059388 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Ruby M V, Lowney Y W. 2012. Selective soil particle adherence to hands:implications for understanding oral exposure to soil contaminants[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 46(23): 12759–12771. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Suzuki G, Kida A, Sakai S, et al. 2009. Existence state of bromine as an indicator of the source of brominated flame retardants in indoor dust[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(5): 1437–1442. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Van den Eede N, Dirtu A C, Ali N, et al. 2012. Multi-residue method for the determination of brominated and organophosphate flame retardants in indoor dust[J]. Talanta, 89: 292–300. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2011.12.031 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Van den Eede N, Dirtu A C, Neels H, et al. 2011. Analytical developments and preliminary assessment of human exposure to organophosphate flame retardants from indoor dust[J]. Environment International, 37(2): 454–461. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2010.11.010 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Van der Veen I, de Boer J. 2012. Phosphorus flame retardants:Properties, production, environmental occurrence, toxicity and analysis[J]. Chemosphere, 88(10): 1119–1153. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.067 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Webster T F, Harrad S, Millette J R, et al. 2009. Identifying transfer mechanisms and sources of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE 209) in indoor environments using environmental forensic microscopy[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(9): 3067–3672. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Wensing M, Uhde E, Salthammer T. 2005. Plastics additives in the indoor environment-flame retardants and plasticizers[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 339(1/3): 19–40. |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | Weschler C J, Nazaroff W W. 2008. Semivolatile organic compounds in indoor environments[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 42(40): 9018–9040. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.052 |

| [${referVo.labelOrder}] | 张月. 2014. 国内外阻燃剂市场分析[J]. 精细与专用化学品, 2014, 22(8): 20–24. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37