2. 宁波诺丁汉大学化学与环境工程系, 宁波 315100;

3. 杭州市气象局, 杭州 310051;

4. 宁波市北仑区气象局, 宁波 315826

2. Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo 315100;

3. Hangzhou Meteorological Bureau, Hangzhou 310051;

4. Ningbo Beilun Meteorological Bureau, Ningbo 315826

真菌气溶胶是生物气溶胶的一种, 具体是指分散相中含有真菌孢子或菌丝的气溶胶.研究发现, 真菌气溶胶等会对人体造成很大的影响, 如感染、过敏和毒性反应等(Oliveira et al., 2005), 尤其是与细颗粒物相关的真菌孢子对人体健康的影响尤为显著(Gorny et al., 2002), 并且真菌气溶胶可以传输几百至几千公里从而影响区域大气环境(Mims et al., 2004).阿糖醇(Arabitol)和甘露醇(Mannitol)是真菌细胞壁的能量贮存物质(Zhang et al., 2010), 其含量多少与真菌气溶胶数目高度相关(Bauer et al., 2008), 在生物质燃烧过程中可以从真菌细胞壁挥发到大气中, 因此, 它们被广泛用作真菌气溶胶有机示踪物(Bauer et al., 2008;Buiarelli et al., 2013;Elbert et al., 2007).

国内外学者针对真菌气溶胶已开展了较多的研究.Fu等(2012)研究发现, 在东亚地区的颗粒物中含有大量的真菌孢子.Zhang等(2010)利用生物化学技术发现, 在中国海南岛热带雨林地区, 真菌孢子对PM10和有机碳的质量贡献分别达到18.2%和26.1%.Yang等(2012)在四川盆地的研究发现, 真菌大量存在于植物、地表土壤等环境中, 野外火灾时大气气溶胶中甘露醇和阿糖醇的浓度会急剧上升.杜睿等(2010)研究了北京及周边地区真菌气溶胶的菌群种类及其粒径分布的季节变化特征.路瑞等(2017)研究了西安市不同天气条件下, 特别是霾天可培养细菌和真菌气溶胶的浓度和粒径分布特征.还有学者对西西伯利亚南部地区(Borodulin et al., 2005)、新加坡(Zuraimi et al., 2009), 以及我国的青岛市(Li et al., 2011)、南京市(陈梅玲等, 2000)等地真菌等微生物气溶胶的季节分布和粒径分布特征进行了研究.长三角地区植被覆盖率高, 但有关该地真菌气溶胶的研究相对较少, 对浙北地区的报道更少.

目前, 国内对真菌等微生物气溶胶的研究主要集中在菌群种类、季节分布和粒径分布特征等方面, 对真菌气溶胶示踪物及其来源分析的研究相对较少.真菌气溶胶有很多来源, 生物质燃烧是其最主要的产生途径(Yang et al., 2012).森林大火、木头和庄稼废弃物的燃烧, 以及家庭生物燃料燃烧能够不同程度的扩散真菌孢子(Pisaric, 2002).除了生物质燃烧, 真菌气溶胶也可能来源于土壤、植被、水和人类活动(Emygdio et al., 2018;Liang et al., 2017).基于此, 本文利用高效液相色谱-串联质谱仪分析PM2.5中真菌气溶胶示踪物阿糖醇和甘露醇的浓度, 研究浙北地区真菌气溶胶的季节性变化特征及其来源, 以期更好地掌握浙北地区大气气溶胶的特征, 并为浙北地区大气污染控制提供科学依据.

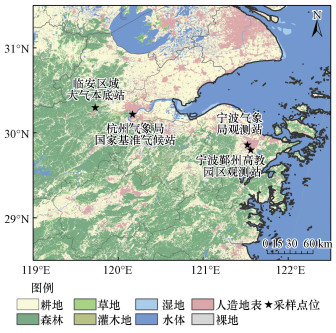

2 采样和分析(Samples and analysis) 2.1 采样站点本文选取了浙北地区4个观测站点, 具体位置如图 1所示.其中, 临安区域大气本底站(LRABS, 30.30°N, 119.73°E)为偏远地区观测点, 处于杭州市所辖临安市郊区, 是隶属于世界气象组织全球大气观测网络的本底监测站.监测站周围是农田和森林, 受到工业化和交通类排放的影响较小.杭州气象局国家基准气候站(HMB, 30.22°N, 120.17°E)为城区观测点, 位于杭州市区中心人口密集区域, 周围200 m区域内有交通密集的道路.宁波气象局观测站(NMB, 29.86°N, 121.52°E)为城区观测点, 位于宁波城市中心主干道——气象路上, 与居民住宅区毗邻, 距离机场高架桥约1 km, 省际高速约500 m.宁波鄞州高教园区观测站(UNNC, 29.80°N, 121.56°E)为城郊观测点, 位于宁波市南部的大学园区宁波诺丁汉大学内, 距离中心商业区约10 km, 该区域作为可同时被城区和郊区排放污染源影响的中间过渡区域.

|

| 图 1 采样点位置 Fig. 1 Locations of sampling sites |

4个站点从2014年12月—2015年11月每6 d 1次进行同步PM2.5采样, 除宁波气象局观测站由于采样器故障采集了51个样品外, 其它站点均采集61个样品.使用武汉天虹中流量采样器(TH-150CIII)采样, 配直径90 mm的石英膜(Whatman), 采样流速为80 L·min-1;每月在这4个采样点取1次空白样本.滤膜使用前在550 ℃的马弗炉内烘烤5 h以去除残留的有机杂质.滤膜在采样前后皆在恒温((22±1) ℃)、恒湿(30%±5%)条件下平衡24 h, 使用微量天平(SE2-F, 赛多利斯, 精确度0.1 μg)进行称重.然后将滤膜包裹在烘烤过的铝箔中, 存储在-20 ℃以下直至进行样品分析.

2.3 实验方法使用高效液相色谱-串联质谱仪(HPLC-MSMS)方法检测2种真菌气溶胶示踪物(阿糖醇、甘露醇)和3种生物质燃烧示踪物(左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖), 详细实验步骤见文献(Xu et al., 2016;徐宏辉等, 2017).阿糖醇、甘露醇、左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖的检测限分别为1.06、0.92、0.31、0.64、0.33 ng·m-3.

7种无机离子(Na+、NH4+、Mg2+、Ca2+、Cl-、NO3-、SO42-)浓度由离子色谱仪(ICS-1600, Dionex, 美国)检测, 详细实验步骤见文献(Xu et al., 2017).由于采样点位于我国东部沿海地区, 海洋的影响不可忽视, 非海盐成分对气溶胶的贡献需要进行量化(Toledano et al., 2012).Na+被假定为仅来自海洋, 那么K+的非海盐(nss)部分可由公式(1)进行计算(Kong et al., , 2014).有机碳(OC)浓度由碳热光学分析仪(2001A, DRI, 美国)检测, 详细实验步骤见文献(杜荣光等, 2013).

|

(1) |

式中, [K+]i和[Na+]i分别代表K+和Na+在气溶胶样本中的浓度;([K+]/[Na+])sea是海水中K+与Na+浓度的比值, 根据海水成分, 比值为0.037(Balasubramanian et al., 2003;Nair et al., 2005).

研究中使用的气象数据(风速、降水、温度及相对湿度)从距离每个采样点最近气象站获取, 具体见表 1.

| 表 1 采样期间浙北地区4个采样点PM2.5的质量浓度和气象参数平均值 Table 1 PM2.5 concentrations and meteorological parameters during the sampling period |

使用美国国家海洋和大气管理局(NOAA)发布的最新混合单粒子拉格朗日积分轨迹模型(HYSPLIT 4.9)模拟气团的后向轨迹.其中, 气象数据来源于美国国家环境预报中心(NCEP)全球数据同化系统(GDAS1, 2006).后向气团轨迹起始时间是在采样当日的9:00(当地时间), 向后追踪96 h, 轨迹起始高度选取距地面500 m, 以确保所模拟的大部分气团位于近地混合层内.另外, 所有获取的轨迹根据不同季节进行聚类分析.火点数据采用基于中分辨率成像光谱仪(MODIS)卫星观测的露天燃烧产品MCD14ML.

3 结果和讨论(Results and discussion) 3.1 浓度水平和季节性变化规律由表 2可知, 浙北地区阿糖醇和甘露醇的年均浓度分别为(5.6±0.7)和(5.7±1.3) ng·m-3, 比北京和华南山区要略低, 但比挪威高得多.4个采样点年均糖醇浓度(阿糖醇和甘露醇浓度之和)从大到小依次为:LRABS (13.3 ng·m-3) > HMB (11.6 ng·m-3) > UNNC (11.5 ng·m-3) > NMB (8.8 ng·m-3).LRABS站点的糖醇浓度最高, 这可能是由于农村地区植被覆盖面积大(图 1), 并且使用生物燃料供暖和烹饪在农村地区仍然常见, 生物质燃烧源贡献较大(Li et al., 2012;Zhang et al., , 2008).NMB站点的糖醇浓度最低, 除了城区低植被覆盖面积的原因外, 该地的低风速((1.6±0.6) m·s-1)是阻碍真菌孢子传输的原因之一, 真菌孢子需要足够的风速才能离开地壳表面进入大气中(Liang et al., 2013).

| 表 2 国内外不同地区阿糖醇和甘露醇的浓度比较 Table 2 The concentration level of arabitol and mannitol in different areas in the world |

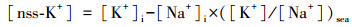

如图 2所示, 浙北地区夏、秋季的阿糖醇和甘露醇浓度水平比冬、春季更高, 这与其它研究结果一致(Burshtein et al., 2011;Yttri et al., 2007).阿糖醇和甘露醇在各个采样点夏季的浓度分别为5.0~7.3 ng·m-3和6.2~13.3 ng·m-3, 夏季阿糖醇和甘露醇的总浓度最高.由表 3可知, 该数据与在葡萄牙、匈牙利的观测结果相近, 但比在香港的浓度要高.农村地区LRABS站点夏季观测到最高的阿糖醇(7.3 ng·m-3)和甘露醇(13.3 ng·m-3)浓度.浙北地区夏季气候具有高温((26.7±0.7) ℃)、高湿((77.8%±3.6%))的特点, 其它研究也表明, 高浓度的糖醇最常出现在温暖潮湿的夏季(Zhang et al., 2008;Zhang et al., 2010).此外, 夏季最高的降雨量也可能是高浓度阿糖醇和甘露醇出现的原因, 相关研究表明, 真菌孢子在雨后贡献了大量的气溶胶粒子(Battarbee et al., 1997), 阿糖醇和甘露醇在气溶胶中的丰度在降雨之后会快速升高(Zhang et al., 2010).

|

| 图 2 4个采样点阿糖醇和甘露醇季平均浓度 Fig. 2 Seasonal averaged concentrations of arabitol and mannitol at four sampling sites |

| 表 3 4个季节无机离子、真菌孢子和生物质燃烧示踪物主成分分析结果 Table 3 Seasonal principal component analysis results of biomarkers and inorganic ions |

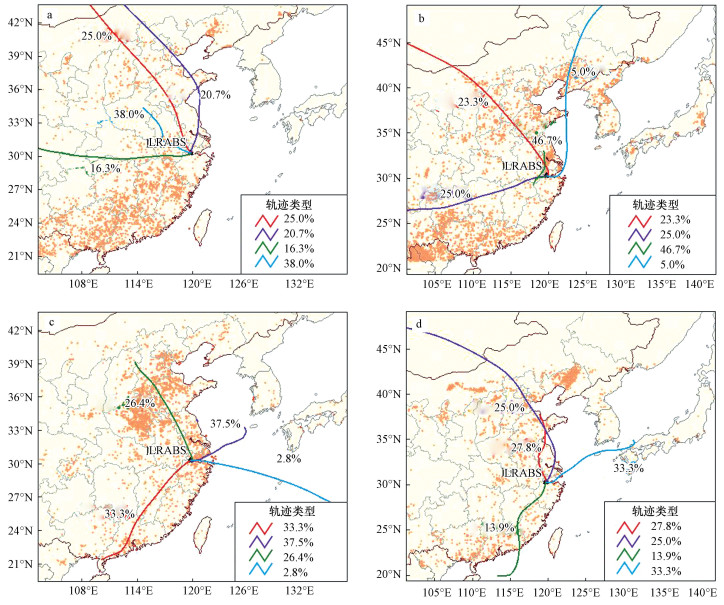

由于4个站点的地理位置比较接近, 气团后向轨迹比较相似, 本文选取了LRABS站点分析了远距离输送气团与真菌气溶胶浓度的关系, 结果如图 3所示.冬季大部分气团来自北和西北方向, 经过严重污染的工业区如京津冀区域, 但经过的火点较少.冬季PM2.5浓度((93.7±36.4) μg·m-3)最高, 但糖醇浓度最低, 可见远距离输送气团中真菌气溶胶的贡献相对较小.春季, 远距离输送气团主要来自西北、西南方向, 46.7%的气团源于当地, 春季糖醇浓度高于冬季, 与秋季接近.夏季有更多的来自海洋的气团从我国东部和西南部传输到长三角地区, 使气候更加温暖潮湿.夏季是长三角地区火点最多的季节, 这更利于当地真菌孢子的传输.秋季, 33.3%的气团来自东部海洋, 有利于真菌气溶胶浓度的上升(Burshtein et al., 2011).

|

| 图 3 各个季节采样期间MODIS火点和临安站点后向气流轨迹群(a.冬季, b.春季, c.夏季, d.秋季) Fig. 3 Seasonal MODIS fire-spots and air mass backward trajectory clusters at LRABS during the sampling period |

通过使用转化因子, 可用真菌气溶胶示踪物估算真菌孢子对大气中OC的贡献.相关研究获得的阿糖醇和甘露醇转化因子分别为:1.2 pg/孢子和1.7 pg/孢子(Bauer et al., 2002), OC为13 pg/孢子(Bauer et al., 2002).为了更好地将本研究的结果与其他研究结果进行比较, 本文应用了转化因子.

浙北地区4个采样点年平均真菌孢子数量为2489~4350个·m-3, 平均值为3372个·m-3.本研究中的孢子数明显低于处于典型生物质燃烧期间的成都(PM2.5中11900~71600个·m-3)和华南沿海山区(PM10中41940个·m-3), 成都在典型生物质燃烧期间的真菌孢子数较多可能是生物燃料燃烧活动更加密集的结果, 而对于华南沿海山区, 因为真菌孢子的尺寸通常在2~10 μm之间, 因此, 可能较多存在于PM10中(Glikson et al., 1995).真菌孢子产生的OC年均值在LRABS、HMB、NMB和UNNC分别为(58.7±38.5)、(48.0±43.5)、(33.1±27.1)和(40.8±32.2) ng·m-3, 分别占上述4个采样点OC的0.6%、0.3%、0.5%和0.4%.这个结果低于中欧森林地区真菌孢子对OC的贡献量, 该地区1.7%的OC产生自真菌孢子(Kourtchev et al., 2009).真菌孢子对OC的贡献在农村采样点LRABS最高.分季节来看, 浙北地区4个采样点夏季由真菌孢子贡献的OC浓度最高;如前所述, 这与夏季的高温高湿天气有关.

3.3 来源分析真菌气溶胶来源复杂, 本研究通过对真菌气溶胶示踪物、生物质燃烧示踪物和无机离子等变量进行主成分分析来解析真菌气溶胶及PM2.5的来源.应用数理统计软件(SPSS V19. 0)对本研究中4个季节的PM2.5样品中2种真菌气溶胶示踪物(阿糖醇和甘露醇)、4种生物质燃烧示踪物(左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖、nss-K+)和7种无机离子(Na+、NH4+、Mg2+、Ca2+、Cl-、NO3-、SO42-)总计13个变量进行主成分分析, 提取特征值大于1的因子, 并采用正交旋转使不同组分的因子载荷差异化便于进行因子识别, 特征组分因子载荷值>0.5用作识别因子, 具体结果列于表 3中.

主成分分析结果显示, 生物质燃烧示踪物和真菌气溶胶示踪物在整个采样过程中几乎都包含在同一个因子中, 表明浙北地区PM2.5中的真菌气溶胶持续受到生物燃料燃烧的影响.

2014年冬季, 因子1中阿糖醇、左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖、nss-K+、Na+、NH4+、Cl-、NO3-和SO42-载荷较大, 占总方差的40.9%, 说明该因子中的真菌气溶胶可能与生物燃料燃烧、化石燃料燃烧等来源相关.因子2主要由阿糖醇、甘露醇和Ca2+组成, 占总方差的25.2%, 说明部分真菌气溶胶可能受到粉尘的影响, 如交通车辆导致的扬尘.有研究表明, 粉尘颗粒可以携带微生物并为它们提供营养(Li et al., 2015).Na+和Mg2+在因子3中载荷较大, 占总方差的7.7%, Na+和Mg2+是海水中最多的两种阳离子(Yang et al., 2012), 说明冬季浙北地区海盐对PM2.5的贡献较少.

2015年春季, 因子1中阿糖醇、左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖、nss-K+、Na+、NH4+和NO3-占总方差的42.1%, 说明真菌气溶胶与生物燃料燃烧、交通源等相关.因子2中Mg2+和Ca2+占总方差的19.7%, 说明地壳粉尘来源对PM2.5的贡献(Zhang et al., 2007).因子3中Na+和Cl-载荷较大, 占总方差的12.8%, 说明春季浙北地区一部分PM2.5来自于海盐.

2015年夏季, 因子1由nss-K+、NH4+、Cl-、NO3-和SO42-组成, 占总方差的27.5%, 说明PM2.5主要与化石燃料源相关, 如煤炭燃烧和交通排放, 这类源对真菌气溶胶没有贡献.因子2中仅含有生物燃料燃烧示踪物(左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖)和真菌孢子示踪物(阿糖醇、甘露醇), 占总方差的23.5%, 主要来源为生物质燃烧.夏季真菌气溶胶示踪物的含量和生物燃料燃烧密切相关.例如, UNNC采样点6月11日阿糖醇(11.3 ng·m-3)和甘露醇(14.9 ng·m-3)的浓度最高, 同日左旋葡聚糖(114.4 ng·m-3)、甘露聚糖(9.1 ng·m-3)、半乳聚糖(3.7 ng·m-3)和nss-K+(0.51 μg·m-3)也是最高的.因子3解释了13.3%的变化量, Na+和Ca2+载荷较大.因子4仅与Mg2+有关, 解释了8.7%的变化量.这2个因子共同说明了长三角地区海盐和地壳粉尘对PM2.5的影响.

2015年秋季, 阿糖醇、左旋葡聚糖、甘露聚糖、半乳聚糖、nss-K+、NH4+、NO3-和SO42-共同组成因子1, 占总方差的42.0%, 表明因子1主要受到生物质燃烧、真菌孢子释放和化石燃料燃烧的影响.因子2和因子3主要与Cl-和Na+相关, 分别占总方差的15.8%和13.6%, Cl-和Na+并未归类到同一因子中, 说明这两种成分并非高度相关, 表明Cl-的污染源可能主要是煤的燃烧, 而Na+则主要是海盐.因子4解释了10.6%的变化量, 主成分为Mg2+和Ca2+, 说明PM2.5受到地壳粉尘的影响.

4 结论(Conclusions)浙北地区PM2.5中阿糖醇和甘露醇的年均浓度分别为(5.6±0.7)和(5.7±1.3) ng·m-3, 略低于北京、华南山区等地.由于该地区夏季频繁的生物质燃烧和温暖湿润的气候条件促进了真菌孢子的释放, 真菌气溶胶示踪物夏季浓度最高.真菌孢子对PM2.5中有机碳的贡献相对较小(< 1%).PCA分析显示, 浙北地区大气中的真菌气溶胶持续受到生物质燃烧的影响.另外, 气团后向轨迹结果表明, 真菌气溶胶的浓度主要受局地源的影响, 远距离输送的气团对真菌气溶胶的贡献较少.

Balasubramanian R, Qian W B, Decesari S, et al. 2003. Comprehensive characterization of PM2.5 aerosols in Singapore[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 108(D16): 4523.

DOI:10.1029/2002JD002517

|

Battarbee J L, Rose N L, Long X Z. 1997. A continuous, high resolution record of urban airborne particulates suitable for retrospective microscopical analysis[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 31(2): 171–181.

DOI:10.1016/1352-2310(96)00195-1

|

Bauer H, Claeys M, Vermeylen R, et al. 2008. Arabitol and mannitol as tracers for the quantification of airborne fungal spores[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 42(3): 588–593.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.10.013

|

Bauer H, Kasper-Giebl A, Zibuschka F, et al. 2002. Determination of the carbon content of airborne fungal spores[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 74(1): 91–95.

DOI:10.1021/ac010331+

|

Borodulin A I, Safatov A S, Shabanov A N, et al. 2005. Physical characteristics of concentration fields of tropospheric bioaerosols in the South of Western Siberia[J]. Journal of Aerosol Science, 36(5/6): 785–800.

|

Buiarelli F, Canepari S, Di Filippo P, et al. 2013. Extraction and analysis of fungal spore biomarkers in atmospheric bioaerosol by HPLC-MS-MS and GC-MS[J]. Talanta, 105: 142–151.

DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2012.11.006

|

Burshtein N, Lang-Yona N, Rudich Y. 2011. Ergosterol, arabitol and mannitol as tracers for biogenic aerosols in the eastern Mediterranean[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 11(2): 829–839.

DOI:10.5194/acp-11-829-2011

|

陈梅玲, 胡庆轩. 2000. 南京市大气微生物污染情况调查[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2000, 16(6): 504–505.

DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-0580.2000.06.015 |

杜荣光, 齐冰, 徐宏辉, 等. 2013. 杭州市PM2.5中碳气溶胶污染特征[J]. 环境化学, 2013, 32(12): 2400–2401.

DOI:10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2013.12.028 |

杜睿, 周宇光. 2010. 北京及周边地区大气近地面层真菌气溶胶的变化特征[J]. 中国环境科学, 2010, 30(3): 296–301.

|

Elbert W, Taylor P E, Andreae M O, et al. 2007. Contribution of fungi to primary biogenic aerosols in the atmosphere:wet and dry discharged spores, carbohydrates, and inorganic ions[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 7(17): 4569–4588.

DOI:10.5194/acp-7-4569-2007

|

Emygdio A P M, Degobbi C, Gonçalves F L T, et al. 2018. One year of temporal characterization of fungal spore concentration in São Paulo metropolitan area, Brazil[J]. Journal of Aerosol Science, 115: 121–132.

DOI:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2017.07.003

|

Fu P, Kawamura K, Kobayashi M, et al. 2012. Seasonal variations of sugars in atmospheric particulate matter from Gosan, Jeju Island:Significant contributions of airborne pollen and Asian dust in spring[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 55(3): 234–239.

|

Glikson M, Rutherford S, Simpson R W, et al. 1995. Microscopic and submicron components of atmospheric particulate matter during high asthma periods in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 29(4): 549–562.

DOI:10.1016/1352-2310(94)00278-S

|

Gorny R L, Reponen T, Willeke K, et al. 2002. Fungal fragments as indoor air biocontaminants[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 68(7): 3522–3531.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.7.3522-3531.2002

|

Hu D, Bian Q, Li T W Y, et al. 2008. Contributions of isoprene, monoterpenes, beta-caryophyllene, and toluene to secondary organic aerosols in Hong Kong during the summer of 2006[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 113: D22206.

DOI:10.1029/2008JD010437

|

Ion A C, Vermeylen R, Kourtchev I, et al. 2005. Polar organic compounds in rural PM(2.5) aerosols from K-puszta, Hungary, during a 2003 summer field campaign:Sources and diel variations[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 5: 1805–1814.

DOI:10.5194/acp-5-1805-2005

|

Kong S, Wen B, Chen K, et al. 2014. Ion chemistry for atmospheric size-segregated aerosol and depositions at an offshore site of Yangtze River Delta region, China[J]. Atmospheric Research, 147-148: 205–226.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosres.2014.05.018

|

Kourtchev I, Copolovici L, Claeys M, et al. 2009. Characterization of atmospheric aerosols at a forested site in central Europe[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(13): 4665–4671.

|

Li J J, Wang G H, Zhou B H, et al. 2012. Airborne particulate organics at the summit (2060 m, a.s.l.) of Mt.Hua in central China during winter:Implications for biofuel and coal combustion[J]. Atmospheric Research, 106: 108–119.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosres.2011.11.012

|

Li M, Qi J, Zhang H, et al. 2011. Concentration and size distribution of bioaerosols in an outdoor environment in the Qingdao coastal region[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 409(19): 3812–3819.

DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.06.001

|

Li Y P, Fu H L, Wang W, et al. 2015. Characteristics of bacterial and fungal aerosols during the autumn haze days in Xi'an, China[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 122: 439–447.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.09.070

|

Liang L, Engling G, Du Z, et al. 2017. Contribution of fungal spores to organic carbon in ambient aerosols in Beijing, China[J]. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 8(2): 351–358.

DOI:10.1016/j.apr.2016.10.007

|

Liang L L, Engling G, He K B, et al. 2013. Evaluation of fungal spore characteristics in Beijing, China, based on molecular tracer measurements[J]. Environmental Research Letters, 8(1): 014005.

DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/014005

|

路瑞, 李婉欣, 宋颖, 等. 2017. 西安市不同天气下可培养微生物气溶胶浓度变化特征[J]. 环境科学研究, 2017, 30(7): 1012–1019.

|

Mims S A, Mims F M. 2004. Fungal spores are transported long distances in smoke from biomass fires[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 38(5): 651–655.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2003.10.043

|

Nair P R, Parameswaran K, Abraham A, et al. 2005. Wind-dependence of sea-salt and non-sea-salt aerosols over the oceanic environment[J]. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, 67(10): 884–898.

DOI:10.1016/j.jastp.2005.02.008

|

Oliveira M, Ribeiro H, Abreu I. 2005. Annual variation of fungal spores in atmosphere of Porto:2003[J]. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 12(2): 309–315.

|

Pio C A, Legrand M, Alves C A, et al. 2008. Chemical composition of atmospheric aerosols during the 2003 summer intense forest fire period[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 42(32): 7530–7543.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.05.032

|

Pisaric M F J. 2002. Long-distance transport of terrestrial plant material by convection resulting from forest fires[J]. Journal of Paleolimnology, 28(3): 349–354.

DOI:10.1023/A:1021630017078

|

Toledano C, Cachorro V E, Gausa M, et al. 2012. Overview of sun photometer measurements of aerosol properties in Scandinavia and Svalbard[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 52(0): 18–28.

|

徐宏辉, 徐婧莎, 何俊, 等. 2017. 高效液相色谱-三重四极杆质谱法快速测定真菌气溶胶示踪物[J]. 环境化学, 2017, 36(12): 2683–2689.

DOI:10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2017042001 |

Xu J S, Xu H H, Xiao H, et al. 2016. Aerosol composition and sources during high and low pollution periods in Ningbo, China[J]. Atmospheric Research, 178-179: 559–569.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosres.2016.05.006

|

Xu J S, Xu M X, Snape C, et al. 2017. Temporal and spatial variation in major ion chemistry and source identification of secondary inorganic aerosols in Northern Zhejiang Province, China[J]. Chemosphere, 179: 316–330.

DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.119

|

Yang Y H, Chan C Y, Tao J, et al. 2012. Observation of elevated fungal tracers due to biomass burning in the Sichuan Basin at Chengdu City, China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 431: 68–77.

DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.033

|

Yttri K E, Dye C, Kiss G. 2007. Ambient aerosol concentrations of sugars and sugar-alcohols at four different sites in Norway[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 7(16): 4267–4279.

DOI:10.5194/acp-7-4267-2007

|

Zhang T, Claeys M, Cachier H, et al. 2008. Identification and estimation of the biomass burning contribution to Beijing aerosol using levoglucosan as a molecular marker[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 42(29): 7013–7021.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.04.050

|

Zhang T, Engling G, Chan C Y, et al. 2010. Contribution of fungal spores to particulate matter in a tropical rainforest[J]. Environmental Research Letters, 5(2): 024010.

DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/5/2/024010

|

Zhang W, Guo J H, Sun Y L, et al. 2007. Source apportionment for, urban PM10 and PM2.5 in the Beijing area[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 52(5): 608–615.

DOI:10.1007/s11434-007-0076-5

|

Zuraimi M S, Fang L, Tan T K, et al. 2009. Airborne fungi in low and high allergic prevalence child care centers[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 43(15): 2391–2400.

DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.02.004

|

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38