双氯芬酸(Diclofenac, DCF)具有较强的抗炎、解热、止痛作用, 被广泛用于风湿性关节炎、多种发热症状的治疗, 是全球使用量最大的非甾体抗炎药之一(Brozinski et al., 2013; McGettigan et al., 2013).大部分DCF以母体药物或经生物体以代谢产物的形式进入城市污水, 目前已成为水环境中高频检出的新兴污染物(Brozinski et al., 2013).污水处理厂是DCF的主要受纳体和进入水环境的主要途径, 据相关研究报道, 污水处理厂进水中DCF的最大浓度在0.44~7.15 μg·L-1之间, 且不同污水处理工艺对DCF的去除率差异较大(21%~61%)(Comeau et al., 2008; Duan et al., 2013; 温智皓等, 2013).DCF长期暴露于环境中会干扰生物体的正常生理功能(Lonappan et al., 2016), 已有研究证明, 5 μg·L-1 DCF暴露可使鳟鱼肝脏发生组织病变(Hoeger et al., 2005), 低浓度DCF即会对生物产生毒性作用.由于DCF具有持久性、生物活性较高的特点, 环境中积累的DCF会对生态系统造成潜在不利影响(Vieno et al., 2014).

随着城市污水中DCF浓度的日渐增加, 近年来许多学者对DCF在污水处理系统中的转化、去除及不同操作条件对DCF去除的影响等进行了研究(Kruglova et al., 2014; Fernandez-Fontaina et al., 2016).例如, Osorio等(2016)检测了污水处理厂中DCF的含氮转化产物, 并指出DCF与其转化产物在毒性上具有协同作用;Vieno等(2014)研究发现, 活性污泥法对DCF的去除效果优于膜生物反应器;Fernandez等(2016)提出, 硝化细菌的增加有利于DCF的生物降解;Salima等(2017)从活性污泥中分离出了能有效降解DCF的特定菌株E.hormaechei.目前, 生物处理法已被广泛应用于污水处理厂以去除各种有机物, 在此过程中活性污泥微生物发挥着关键作用, 污水中的DCF可能会对微生物的活性产生影响, 进而影响微生物的降解作用(Kraigher et al., 2011; Diniz et al., 2015).然而, 关于DCF长期存在对污水处理系统活性污泥处理性能和微生物群落的影响报道较少, DCF与污水处理厂出水水质和微生物群落之间的关系尚不明确.为此, 本研究在环境浓度DCF(5和50 μg·L-1)压力下运行实验室规模序批式反应器(SBR), 达到稳定状态后, 定期测量化学需氧量(COD)、氨氮(NH4+-N)、总氮(TN)浓度, 分析活性污泥关键酶活性、胞外聚合物(EPS)含量、磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA)组成, 并结合16S rRNA基因焦磷酸测序结果探究微生物群落结构的变化, 以期进一步了解DCF选择性压力与SBR出水水质之间的关系, 阐明DCF对活性污泥生理生化性能和微生物群落结构的影响, 为污水处理过程的稳定运行和DCF的有效去除提供参考.

2 材料和方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 实验材料双氯芬酸钠(Diclofenac sodium salt)为分析纯(纯度≥98%), 购自美国Sigma公司;甲醇、乙腈和乙酸均为色谱纯, 购自德国Merck公司;其他常规化学试剂均为分析纯, 购自南京化学试剂有限公司.

实验所接种的活性污泥取自南京某市政污水处理厂的好氧曝气池, 该厂采用缺氧-好氧(A/O)生物处理工艺.在反应器接种前将活性污泥曝气48 h, 混合液挥发性悬浮固体(MLVSS)浓度为3.54 g·L-1, 污泥沉降指数(SVI)为110~120 mg·L-1, 说明接种污泥具有良好的松散程度和凝聚沉降性能.

2.2 反应装置及运行条件将活性污泥接种在有效体积为4 L的SBR中, 进行为期120 d的DCF暴露实验.SBR每天运行3个周期, 每个运行周期(8 h)由进料(60 min)、反应(330 min)、沉淀(30 min)、出水(10 min)和闲置(50 min)组成.为模拟污水中DCF浓度, 向反应器中投加DCF储备液并控制进水DCF浓度分别为5 μg·L-1(R5)和50 μg·L-1(R50), 无DCF添加的反应器用作对照(R0).制备合成污水模拟城市污水组成(Kruglova et al., 2014), 具体成分如表 1所示.整个实验温度控制在(21±1) ℃, pH控制在7.0~8.0, 污泥停留时间(SRT)为20 d, 悬浮固体(MLSS)浓度为(3.5±0.2) g·L-1, 每个运行周期中SBR的出水体积为2.4 L.SBR进水COD、NH4+-N和总磷(TP)的初始浓度分别为300、20和3 mg·L-1, 反应器在3个SRT(60 d)之后达到稳定运行.

| 表 1 模拟污水的组成 Table 1 Composition of synthetic wastewater |

COD、NH4+-N、TN等基础指标的检测均参照国标法(国家环境保护总局, 2002), 溶解氧浓度、pH和温度借助溶氧仪(SG6, METTLER TOLEDO Inc., USA)和pH计(FE20, METTLER TOLEDO Inc., USA)测定.使用相应检测试剂盒(南京生物工程研究所)检测超氧化物歧化酶(SOD)和琥珀酸脱氢酶(SDH)的活性, 使用微量BCA蛋白质定量试剂盒(南京生物工程研究所)测定蛋白质浓度, 通过总蛋白质浓度将酶活性归一化(Jiang et al., 2017).使用热提法提取活性污泥中的EPS(李继宏等, 2013), 以蛋白质(PN)和胞外多糖(PS)表征(Zhu et al., 2015), 采用改良的Lowry法测定PN浓度(Frølund et al., 1996), 采用以葡萄糖为标准品的硫酚法测定PS浓度(Dubois et al., 1956).

根据Niu等(2012)描述的方法提取污泥样品中的PLFA并采用气相色谱(Agilent 7890, USA)进行检测, 使用MIDI Sherlock微生物鉴定系统(MIDI, Newark, DE)分析其结果.基于PLFA的检测结果, 计算香农-威尔多样性指数(Shannon-Wiener Index, H)以表征微生物的丰富度和均匀度(Niu et al., 2013), 计算公式如下:

|

(1) |

式中, s为样品测得的PLFA总数, pi为样品气相色谱分析的各PLFA峰面积与总面积的百分比.

从3个SBR反应器底部收集活性污泥用于16S rRNA基因焦磷酸测序(Zhu et al., 2015), 整个测序过程包括DNA提取、16S rRNA基因PCR扩增和PCR产物纯化.通过Fast DNA TM Spin Kit for Soil(MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA)提取DNA, 基于细菌16S rRNA基因V1~V2区通用引物对DNA样品进行PCR扩增, PCR扩增过程中所用的正向引物序列为5′-AGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3′, 反向引物序列为5′-TGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′.PCR扩增产物采用纯化试剂盒(Cycle-Pure Kit, OMEGA Bio-tek, Inc.)进行纯化, 并将纯化产物送至江苏中宜金大分析检测有限公司使用Illumina测序平台进行高通量测序分析.

2.4 数据分析所有样品至少分析3次, 结果以平均值±标准偏差表示.使用Origin 9.0软件处理常规水质指标的数据.单因素方差分析(ANOVA)用于评估方差的同质性, 当p < 0.05时, 认为样品间存在显著性差异, 使用SPSS Statistics 22.0进行数据的统计分析.

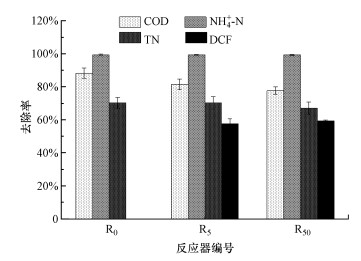

3 结果与讨论(Results and discussion) 3.1 环境浓度DCF对SBR出水水质的影响0、5、50 μg·L-1 DCF压力下SBR系统COD、NH4+-N、TN的去除情况如图 1所示.在SBR稳定运行阶段, R0、R5和R50的COD去除率分别为88.27%±3.17%、81.45%±3.29%和77.64%±2.20%, NH4+-N去除率均超过99%, TN去除率在70%上下波动.DCF压力下COD的整体去除效果受到明显抑制(p < 0.05), 有研究表明, 10 mg·L-1抗生素的冲击也会导致活性污泥COD去除率的下降(Zhang et al., 2016b).5 μg·L-1和50 μg·L-1 DCF压力下NH4+-N的去除没有明显差异(p>0.05), TN的去除仅显示出轻微的波动, 表明环境浓度DCF对SBR的脱氮性能影响较小.短期硝化实验结果表明, 活性污泥的脱氮效果不受低于40 μg·L-1的混合抗生素的抑制(Schmidt et al., 2012), 9 μmol·L-1和32 μmol·L-1的氧氟沙星、诺氟沙星和环丙沙星对氮的去除影响同样较小(Amorim et al., 2014).

|

| 图 1 DCF对SBR出水水质的影响 Fig. 1 Effect of DCF on the treatment efficiency of SBR |

R5和R50的DCF去除率分别为57.64%±2.92%和59.45%±0.44%, 这与Gros等(2010)报道的污水处理厂中DCF的去除率相近, 且随着DCF浓度的增加, DCF的去除率呈上升趋势.Xue等(2010)研究发现, DCF的去除受污泥溶解氧等条件的影响, 在污水处理厂厌氧-缺氧-好氧-膜生物反应器的厌氧池中, DCF的去除率较高.在中性实验条件下由于电离作用, DCF难以吸附到污泥中(Nikolaou et al., 2007);Kruglova等(2014)观察进水中(1.0±0.4) μg·L-1 DCF在活性污泥中的降解情况时发现, DCF的生物降解速率常数介于0.5~1.0 L·g-1·d-1之间, 说明DCF可被适度生物降解;有研究报道从活性污泥中分离出了能够降解DCF的菌株(Aissaoui et al., 2017; Bessa et al., 2017).由此推断, 本研究R5和R50中DCF的去除是由活性污泥中相应微生物降解引起的.

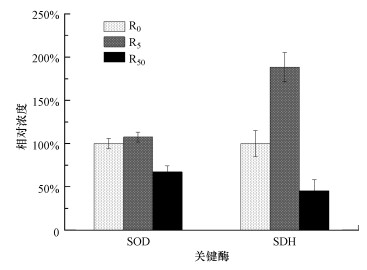

3.2 环境浓度DCF对活性污泥关键氧化酶活性的影响超氧化物歧化酶(SOD)是一种普遍存在于微生物体中的清除体内自由基(以O2-为主)的抗氧化酶, 是氧化应激的重要抗氧化酶和指标之一(Diniz et al., 2015);琥珀酸脱氢酶(SDH)是三羧酸循环的关键酶, 能够反映线粒体功能(Sastre, 2003).为了评价DCF对污泥关键氧化酶活性的影响, 反应器运行至100 d时从活性污泥中提取SOD和SDH以评估微生物的应激作用.图 2给出了相较于对照组(100%)各反应器中活性污泥的关键氧化酶相对活性的变化, 结果显示, SOD活性(以prot计)从(32.16±0.14) U·mg-1(R0)增加到(34.56±0.09) U·mg-1(R5), 但在R50中下降至(21.6±0.24) U·mg-1;SDH活性(以prot计)与SOD活性具有相似的变化趋势, 即从(5.44±0.06) U·mg-1(R0)变为(10.25±0.12) U·mg-1(R5)再下降至(2.47±0.04) U·mg-1(R50).低浓度DCF在一定程度上能增强部分微生物的活性, 但高浓度条件下由于DCF的毒性效应微生物活性被抑制.

|

| 图 2 DCF对活性污泥关键氧化酶活性的影响 Fig. 2 Effect of DCF on critical oxidase activities of activated sludge |

与对照组对比, 5 μg·L-1 DCF提高了SOD和SDH活性.SOD可通过清除自由基来降低抗炎药的毒性(Grekova-Vasileva et al., 2014; El-Megharbel et al., 2015), SOD活性的升高表明环境浓度DCF可诱导活性污泥中微生物的氧化应激作用, 以抵抗DCF对污泥微生物的刺激.SDH可为呼吸链提供电子, 在原核细胞中广泛存在(Sastre, 2003), 5 μg·L-1 DCF下微生物通过提高SDH活性来增强三羧酸循环, 从而为微生物的应激作用提供更多的能量(Jiang et al., 2017).与5 μg·L-1 DCF的结果相反, 50 μg·L-1 DCF显著抑制了SOD和SDH活性(p < 0.05).研究表明, 高浓度偶氮化合物会对活性污泥代谢产生负面影响从而使SOD活性降低(Grekova-Vasileva et al., 2014);游偲(2012)在研究石油烃对沙蚕抗氧化酶系统的影响时发现, SOD活性先被诱导而后因毒性被抑制.SOD活性被抑制说明50 μg·L-1的DCF抑制了微生物清除自由基的能力并对微生物造成了一定的毒性作用.SDH活性明显下降, 说明有氧呼吸过程减少, 可能是DCF对线粒体功能造成损害或影响了微生物的中间代谢(Bellavite et al., 2010).其他学者在研究含重金属、农药的活性污泥的毒性作用时同样发现受试动物体内SDH活性显著降低(Bag et al., 1999), 5 μg·L-1非甾体抗炎药混合物也造成了SDH活性的下降(Jiang et al., 2017).

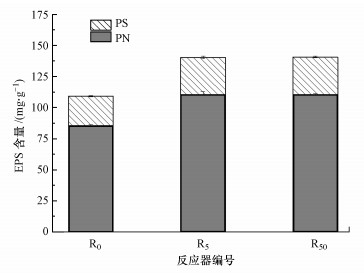

3.3 环境浓度DCF对活性污泥EPS含量的影响难生物降解的污染物会影响活性污泥微生物正常的生理生化性能, EPS作为活性污泥的重要组成部分, 既能保护微生物抵抗外界压力和刺激, 也可表征活性污泥的物化特征和生物性能(Shi et al., 2013).为研究DCF对活性污泥微生物生理生化性能的影响, 观察了稳定阶段(第100 d)活性污泥中PN和PS的变化, 结果如图 3所示.由图可知, 各反应器中PN和PS含量(均以VSS计)分别出现一定程度的增加, 在R0、R5和R50中PN含量分别为85.41、110.54和110.44 mg·g-1, PS含量分别为23.81、29.85和30.25 mg·g-1, PN含量增加更为明显.Zhao等(2018)研究表明, 厌氧氨氧化污泥中胞外PN/PS升高可明显增加细胞的疏水性和聚集能力, 对污泥性能的稳定具有促进作用.EPS含量的增加表明5 μg·L-1 DCF引起了微生物的保护性反应以抵抗DCF的毒性效应.Wang等(2016)曾报道Cd(Ⅱ)浓度增加导致EPS含量增加, 细菌分泌更多的EPS以降低重金属对细菌的毒性;Delgado等(2010)也指出, 在使用磷酰胺药物的情况下, 微生物会产生更多的EPS作为保护屏障.50 μg·L-1 DCF存在下反应器中EPS含量与R5中相近, 推测是高浓度DCF的毒性对微生物造成了一定危害进而抑制了微生物分泌更多的EPS.Quan等(2015)的研究结果支持了这一结论, 他们报道不同浓度纳米银存在时的低毒性可能导致污泥中EPS含量增加, 但高毒性可抑制其产生.5 μg·L-1的DCF添加在一定程度上会促进微生物分泌EPS, 但50 μg·L-1的DCF没有使EPS进一步提高.这与氧化酶活性的变化相似, DCF浓度与污泥EPS含量的具体响应关系仍需要进一步研究.

|

| 图 3 DCF对活性污泥EPS含量的影响 Fig. 3 Effect of DCF on EPS content of activated sludge |

PLFA组成可用于分析微生物群落结构(Li et al., 2010).运行结束时从反应器中取污泥测PLFA组成, 结果显示, PLFA的碳链长度主要分布在C12~C20之间, 占优势的PLFA为16:0、18:0、16:1 w7c和18:1 w7c, 根据PLFA结果进一步计算Shannon-Wiener多样性指数, 用于评估微生物种群的整体多样性.结果显示, Shannon-Wiener指数分别为1.65(R0)、1.75(R5)和1.60(R50), 外加5 μg·L-1时DCF微生物群落多样性增加, 当DCF为50 μg·L-1时微生物群落多样性较对照组有所下降.这表明污水低浓度DCF使微生物多样性增加以适应环境胁迫, 而高浓度DCF会对微生物产生毒害作用, 这与酶活性及PLFA分析的结果一致.有研究表明, 抗生素为5 μg·L-1时微生物多样性达到最大值, 且随着抗生素浓度的增加多样性指数降低(Zhang et al., 2016b), Zhang等(2015)也发现250 μg·L-1布洛芬会导致湿地中微生物群落的多样性显著降低.

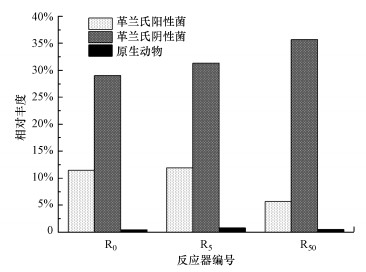

PLFA测定结果中不同特征脂肪酸的相对含量可反映不同类群微生物的相对丰度(Niu et al., 2012; Niu et al., 2013), 如单不饱和脂肪酸和环丙烷脂肪酸可指示革兰氏阴性菌, 利用PLFA生物标记可以表征革兰氏阳性菌、革兰氏阴性菌和原生动物的相对含量(图 4).如图 4所示, DCF对原生动物含量的影响较小, R0和R5之间革兰氏阳性菌和革兰氏阴性菌的相对丰度几乎没有差异(p>0.05);R50相比于R0革兰氏阴性菌的相对丰度从29.03%增加至35.7%, 革兰氏阳性菌的相对丰度从11.46%降至5.68%.革兰氏阴性菌的细胞膜不饱和脂肪酸含量较高使其更加稳定, 能够在环境胁迫下及时做出适应性变化, 改变脂质组成来适应DCF对活性污泥的干扰(Moll et al., 1999;Huang et al., 2009).革兰氏阳性菌细胞结构稳定、刚性强, 无法适应较高的环境压力(Niu et al., 2012).Paje等(2002)研究表明, 100 μg·L-1的DCF对菌落具有选择作用, 会抑制革兰氏阳性菌的生长.

|

| 图 4 DCF对活性污泥优势菌种的影响 Fig. 4 Effect of DCF on dominant bacteria in activated sludge |

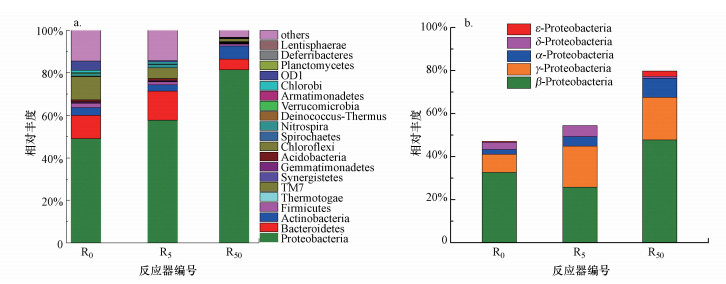

为研究DCF对SBR系统中微生物群落结构和功能的影响, 在SBR运行结束时对空白组和外加DCF实验组进行了16S rRNA基因焦磷酸测序, 图 5a显示了污泥样品在门水平上相对丰度超过0.10%的优势菌分布情况.所有样品中Proteobacteria相对丰度最高, 在R0、R5、R50反应器中的占比分别为48.94%、57.79%、81.48%, 且随DCF浓度的增加有上升趋势.Proteobacteria属革兰氏阴性菌, 这与PLFA得到的优势菌种的变化相符.Proteobacteria对外部环境的适应性最强(Zhang et al., 2016a), 为进一步了解其变化, 本研究对其在纲水平上进行分类, 图 5b为各反应器中Proteobacteria在纲水平上的分布情况.如图所示, β-Proteobacteria(25.9%~47.7%)是列出的5个纲中最主要的类别, 其次是γ-Proteobacteria、α-Proteobacteria和δ-Proteobacteria, ε-Proteobacteria的丰度非常低, 仅在R50反应器中有少量分布.除δ-Proteobacteria外, 其他Proteobacteria丰度在DCF选择压力下均有增加.结果表明, DCF影响了Proteobacteria纲水平上各类微生物的生长, 相关研究证实DCF浓度的增加会导致微生物群落结构更大的变化.β-proteobacteria中含有许多异养型属和一些化能自养型属, 作为环境胁迫下的优势菌, 具有较强的的适应能力(Kraigher et al., 2008).Lawrence等(2007)研究发现, DCF能改变河流生物群落组成并指出10和100 μg·L-1 DCF可使γ-变形菌显著增加.ε-Proteobacteria常存在于难降解物质存在的微生物系统(刘风华等, 2013).

|

| 图 5 环境浓度DCF下活性污泥微生物门水平群落结构的演变(a)和变形菌的分布(b) Fig. 5 Evolution of microbial population level (a) and distribution of proteobacteria (b) of activated sludge under environmenttal concentration DCF |

另外两种占比较大的是Bacteroidetes和Chloroflexi, 这与Zhang等(2012)研究的来自14个污水处理厂的活性污泥群落分析结果一致, 这3种优势门在3组反应器中分布的总占比达到了63%~92%.有研究发现, 在处理含氟氯烃的污水厂中, 消耗碳水化合物的Chloroflexi也是优势门之一(Kragelund et al., 2007, Miura et al., 2007).Bacteroidetes作为异养微生物, 能够降解高分子有机物如石油烃(Gargouri et al., 2014), 低浓度DCF对其丰度具有促进作用而高浓度DCF抑制其丰度.本研究中各反应器微生物门水平的类型极为相似(90%), 而各门的丰度有显著差异(p < 0.05).在对照组(R0)中, Chloroflexi、OD1和Firmicutes的占比分别为10.98%、4.22%和1.95%.随着DCF的加入, R5和R50中Chloroflexi的丰度分别降低到4.99%和1.38%, OD1丰度分别为0.72%和0.05%, Firmicutes的丰度分别降至1.36%和0.95%.高浓度DCF下Actinobacteria丰度升高至6.17%(p < 0.05), Prior等(2010)发现Actinobacteria分泌的细胞色素P450酶可将DCF羟基化, Pala-Ozkok等(2014)也发现持续暴露在红霉素条件下的活性污泥中Actinobacteria丰度由22%增加至48%, 推测Actinobacteria可能具有降解DCF的潜力.药物的降解主要依赖于活性污泥微生物群落的固有能力(Kraigher et al., 2008), 因此, R5和R50中部分DCF的降解可能是Actinobacteria等特定微生物完成的.

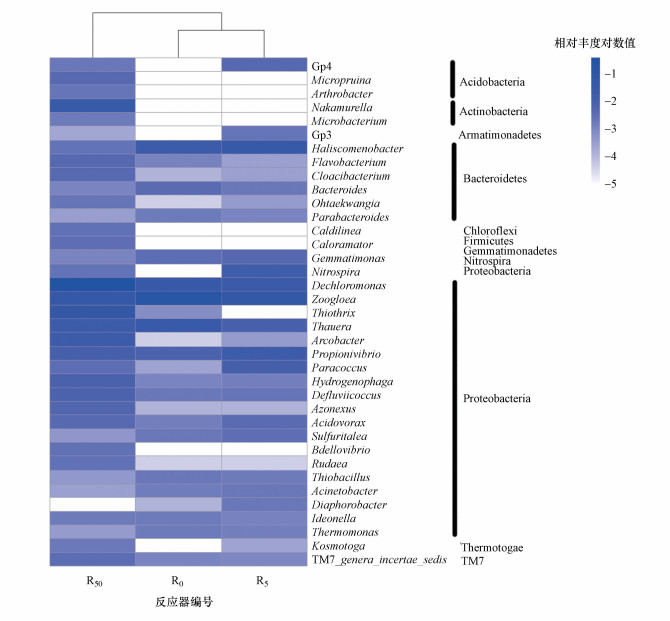

3.6 环境浓度DCF对活性污泥微生物属水平的影响环境浓度DCF下活性污泥微生物属水平的优势菌热图(相对丰度超过0.20%)如图 6所示, Nakamurella, Micropruina、Caloramator、Caldilinea、Bdellovibrio、Arthrobacter和Microbacterium仅在添加50 μg·L-1 DCF的污泥样品中测得, 其中, Micropruina和Arthrobacter均属于酸杆菌门, 推测这些菌属丰度的增加是酸性药物DCF的刺激导致的.有研究表明, Micropruina是一类耐毒性微生物(Wang et al., 2015), Micropruina和Nakamurella具有在恶劣条件下积累能量化合物的能力(Domaradzka et al., 2015), 适应性较强.在R5和R50中, Thauera丰度从3.1%降至0.97%, Nitrospira丰度从1.6%降至0.24%.据报道, Thauera能够代表污水处理过程中的反硝化细菌(Tarlera et al., 2003), Nitrospira是活性污泥中重要的脱氮微生物(Tian et al., 2015), 但反应器中NH4+-N和TN的去除仅显示轻微波动, 这可能是由于Thauera和Nitrospira含量较低及微生物自身的复杂多变性导致的.此外, 还检测到了活性污泥中广泛存在的Dechloromonas(3.7%~35.5%, 平均为13.8%)和Zoogloea(4%~13%, 平均为7.6%)及丰度较低的Haliscomenobacter(0.25%~3.4%, 平均为1.9%)、Propionivibrio(0.8%~1.8%, 平均为1.2%)等.Zoogloea作为菌胶团的主要组成成分, 对环境胁迫具有缓冲作用.本研究中Zoogloea丰度从13.1%(R0)降至4.2%(R50), 说明污水中高浓度DCF对活性污泥微生物菌胶团的形成产生了明显的抑制(Wang et al., 2015), Zoogloea的减少削弱了污泥系统的抗冲击能力, 这与本研究中微生物活性降低的结果一致.随着环境中DCF的积累, 高浓度DCF对微生物群落结构的影响需要进一步研究.

|

| 图 6 环境浓度DCF下活性污泥微生物属水平群落结构热图 Fig. 6 Heat map of microbial genus level of activated sludge under environmental concentration DCF |

1) 环境浓度DCF导致SBR出水COD去除率显著下降(p < 0.05), 对NH4+-N和TN的去除没有明显影响, DCF的去除效果随DCF浓度的增加而提高.

2) SOD和SDH活性在低浓度(5 μg·L-1)DCF的刺激下均有升高, 在高浓度(50 μg·L-1)DCF条件下活性明显下降;与对照组相比, 5和50 μg·L-1 DCF压力下EPS含量明显升高且含量相近, PN含量较PS含量有更显著的增加.

3) 通过Shannon-Wiener指数表明, 环境浓度DCF对微生物群落多样性具有低促高抑作用.DCF对原生动物含量的影响较小, 革兰氏阴性菌的丰度随DCF浓度的增加而升高, 革兰氏阳性菌无法适应环境高浓度DCF的压力导致其丰度下降.

4) 16S rRNA基因焦磷酸测序结果表明, 5~50 μg·L-1 DCF存在的情况下, 活性污泥中门水平上的优势菌为Proteobacteria、Bacteroidetes和Chloroflexi, 其中, Proteobacteria内除δ-Proteobacteria外, 其他Proteobacteria丰度均随DCF选择压力增大逐渐增加.5 μg·L-1 DCF对Bacteroidetes丰度具有促进作用, 而50 μg·L-1 DCF会显著抑制其丰度;Chloroflexi、OD1和Firmicutes在DCF胁迫下丰度下降;污水高浓度DCF下Actinobacteria丰度明显升高.

5) 对活性污泥中属水平上的优势菌进行分析, 50 μg·L-1 DCF刺激了Nakamurella、Micropruina、Caloramator、Caldilinea、Bdellovibrio、Arthrobacter和Microbacterium丰度的增加.脱氮相关微生物Thauera和Nitrospira丰度下降, 高浓度DCF对活性污泥常见菌属Dechloromonas有促进作用, 但对Zoogloea有抑制效果.

Aissaoui S, Ouled-Haddar H, Sifour M, et al. 2017. Metabolic and co-metabolic transformation of diclofenac by Enterobacter hormaechei D15 isolated from activated sludge[J]. Current Microbiology, 74(3): 381–388.

DOI:10.1007/s00284-016-1190-x

|

Amorim C L, Maia A S, Mesquita R B, et al. 2014. Performance of aerobic granular sludge in a sequencing batch bioreactor exposed to ofloxacin, norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin[J]. Water Research, 50: 101–113.

DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.043

|

Bag S, Vora T, Ghatak R, et al. 1999. A study of toxic effects of heavy metal contaminants from sludge-supplemented diets on male Wistar rats[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 42(2): 163–170.

DOI:10.1006/eesa.1998.1736

|

Bellavite P, Chirumbolo S, Marzotto M. 2010. Hormesis and its relationship with homeopathy[J]. Human & Experimental Toxicology, 29(7): 573–579.

|

Bessa V S, Moreira I S, Tiritan M E, et al. 2017. Enrichment of bacterial strains for the biodegradation of diclofenac and carbamazepine from activated sludge[J]. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 120: 135–142.

|

Brozinski J M, Lahti M, Meierjohann A, et al. 2013. The anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac, naproxen and ibuprofen are found in the bile of wild fish caught downstream of a wastewater treatment plant[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(1): 342–348.

|

Comeau F, Surette C, Brun G L, et al. 2008. The occurrence of acidic drugs and caffeine in sewage effluents and receiving waters from three coastal watersheds in Atlantic Canada[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 396(2/3): 132–146.

|

Delgado L F, Schetrite S, Gonzalez C, et al. 2010. Effect of cytostatic drugs on microbial behaviour in membrane bioreactor system[J]. Bioresource Technology, 101(2): 527–536.

DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2009.08.051

|

Diniz M S, Salgado R, Pereira V J, et al. 2015. Ecotoxicity of ketoprofen, diclofenac, atenolol and their photolysis byproducts in zebrafish (Danio rerio)[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 505: 282–289.

DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.103

|

Domaradzka D, Guzik U, Wojcieszyńska D. 2015. Biodegradation and biotransformation of polycyclic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[J]. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 14(2): 229–239.

DOI:10.1007/s11157-015-9364-8

|

Duan Y P, Meng X Z, Wen Z H, et al. 2013. Acidic pharmaceuticals in domestic wastewater and receiving water from hyper-urbanization city of China (Shanghai):Environmental release and ecological risk[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 20(1): 108–116.

DOI:10.1007/s11356-012-1000-3

|

Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, et al. 1956. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 28(3): 350–356.

DOI:10.1021/ac60111a017

|

El-Megharbel S M, Hamza R Z, Refat M S. 2015. Synthesis, spectroscopic and thermal studies of Mg(Ⅱ), Ca(Ⅱ), Sr(Ⅱ) and Ba(Ⅱ) diclofenac sodium complexes as anti-inflammatory drug and their protective effects on renal functions impairment and oxidative stress[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A:Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 135: 915–928.

DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2014.07.101

|

Fernandez-Fontaina E, Gomes I B, Aga D S, et al. 2016. Biotransformation of pharmaceuticals under nitrification, nitratation and heterotrophic conditions[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 541: 1439–1447.

DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.010

|

Frølund B, Palmgren R, Keiding K, et al. 1996. Extraction of extracellular polymers from activated sludge using a cation exchange resin[J]. Water Research, 30(8): 1749–1758.

DOI:10.1016/0043-1354(95)00323-1

|

Gargouri B, Karray F, Mhiri N, et al. 2014. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons-contaminated soil by bacterial consortium isolated from an industrial wastewater treatment plant[J]. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 89(7): 978–987.

|

Grekova-Vasileva M, Topalova Y. 2014. Enzyme activities and shifts in microbial populations associated with activated sludge treatment of textile effluents[J]. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 23(1): 1136–1142.

|

Gros M, Petrovic M, Ginebreda A, et al. 2010. Removal of pharmaceuticals during wastewater treatment and environmental risk assessment using hazard indexes[J]. Environment International, 36(1): 15–26.

DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2009.09.002

|

国家环境保护总局. 2002. 水和废水监测分析方法[M]. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社.

|

Hoeger B, Kollner B, Dietrich D R, et al. 2005. Water-borne diclofenac affects kidney and gill integrity and selected immune parameters in brown trout (Salmo trutta f.fario)[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 75(1): 53–64.

|

Huang H, Zhang S, Wu N, et al. 2009. Influence of Glomus etunicatum/Zea mays mycorrhiza on atrazine degradation, soil phosphatase and dehydrogenase activities, and soil microbial community structure[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41(4): 726–734.

DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.01.009

|

Jiang C, Geng J, Hu H, et al. 2017. Impact of selected non-steroidal anti-inflammatory pharmaceuticals on microbial community assembly and activity in sequencing batch reactors[J]. Plos One, 12(6): e0179236.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0179236

|

Kragelund C, Levantesi C, Borger A, et al. 2007. Identity, abundance and ecophysiology of filamentous Chloroflexi species present in activated sludge treatment plants[J]. Fems Microbiology Ecology, 59(3): 671–682.

DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00251.x

|

Kraigher B, Kosjek T, Heath E, et al. 2008. Influence of pharmaceutical residues on the structure of activated sludge bacterial communities in wastewater treatment bioreactors[J]. Water Research, 42(17): 4578–4588.

DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2008.08.006

|

Kraigher B, Mandic-Mulec I. 2011. Nitrification activity and community structure of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in the bioreactors operated with addition of pharmaceuticals[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 188(1/3): 78–84.

|

Kruglova A, Ahlgren P, Korhonen N, et al. 2014. Biodegradation of ibuprofen, diclofenac and carbamazepine in nitrifying activated sludge under 12 degrees C temperature conditions[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 499(1): 394–401.

|

Lawrence J R, Swerhone G D W, Topp E, et al. 2007. Structural and functional responses of river biofilm communities to the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory diclofenac[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 26(4): 573–582.

DOI:10.1897/06-340R.1

|

李继宏, 单士亮, 李亮, 等. 2013. 膜生物反应器中EPS的提取方法[J]. 环境工程, 2013, 31(3): 10–14.

DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-1556.2013.03.003 |

Li M, Zhou Q, Tao M, et al. 2010. Comparative study of microbial community structure in different filter media of constructed wetland[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 22(1): 127–133.

DOI:10.1016/S1001-0742(09)60083-8

|

刘风华, 宋永会, 曾萍, 等. 2013. 应用16S rDNA克隆文库解析好氧颗粒污泥细菌菌群多样性[J]. 环境污染与防治, 2013, 35(7): 1–6.

DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-3865.2013.07.001 |

Lonappan L, Brar S K, Das R K, et al. 2016. Diclofenac and its transformation products:Environmental occurrence and toxicity-A review[J]. Environment International, 96: 127–138.

DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2016.09.014

|

McGettigan P, Henry D. 2013. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that elevate cardiovascular risk:an examination of sales and essential medicines lists in low-, middle-, and high-income countries[J]. Plos Medicine, 10(2): e1001388.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001388

|

Miura Y, Hiraiwa M N, Ito T, et al. 2007. Bacterial community structures in MBRs treating municipal wastewater:relationship between community stability and reactor performance[J]. Water Research, 41(3): 627–637.

DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2006.11.005

|

Moll D M, Summers R S, Fonseca A C, et al. 1999. Impact of temperature on drinking water biofilter performance and microbial community structure[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 33(14): 2377–2382.

|

Nikolaou A, Meric S, Fatta D. 2007. Occurrence patterns of pharmaceuticals in water and wastewater environments[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 387(4): 1225–1234.

DOI:10.1007/s00216-006-1035-8

|

Niu C, Geng J, Ren H, et al. 2012. The cold adaptability of microorganisms with different carbon source in activated sludge treating synthetical wastewater[J]. Bioresource Technology, 123: 66–71.

DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.110

|

Niu C, Geng J, Ren H, et al. 2013. The strengthening effect of a static magnetic field on activated sludge activity at low temperature[J]. Bioresource Technology, 150: 156–162.

DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.139

|

Osorio V, Sanchis J, Abad J L, et al. 2016. Investigating the formation and toxicity of nitrogen transformation products of diclofenac and sulfamethoxazole in wastewater treatment plants[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 309: 157–164.

DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.02.013

|

Paje M L, Kuhlicke U, Winkler M, et al. 2002. Inhibition of lotic biofilms by diclofenac[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 59(4/5): 488–492.

|

Pala-Ozkok I, Rehman A, Ubay-Cokgor E, et al. 2014. Pyrosequencing reveals the inhibitory impact of chronic exposure to erythromycin on activated sludge bacterial community structure[J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 90: 195–205.

DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2014.06.003

|

Prior J E, Shokati T, Christians U, et al. 2010. Identification and characterization of a bacterial cytochrome P450 for the metabolism of diclofenac[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 85(3): 625–633.

DOI:10.1007/s00253-009-2135-0

|

Quan X, Cen Y, Lu F, et al. 2015. Response of aerobic granular sludge to the long-term presence to nanosilver in sequencing batch reactors:reactor performance, sludge property, microbial activity and community[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 506-507: 226–233.

DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.015

|

Sastre J. 2003. The role of mitochondrial oxidative stress in aging[J]. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 35(1): 1–8.

DOI:10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00184-9

|

Schmidt S, Winter J, Gallert C. 2012. Long-term effects of antibiotics on the elimination of chemical oxygen demand, nitrification, and viable bacteria in laboratory-scale wastewater treatment plants[J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 63(3): 354–364.

DOI:10.1007/s00244-012-9773-4

|

Shi Y, Xing S, Wang X, et al. 2013. Changes of the reactor performance and the properties of granular sludge under tetracycline (TC) stress[J]. Bioresource Technology, 139: 170–175.

DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.037

|

Tarlera S, Denner E B. 2003. Sterolibacterium denitrificans gennov., sp.nov., a novel cholesterol-oxidizing, denitrifying member of the beta-Proteobacteria[J]. International Journal of Systematic & Evolutionary Microbiology, 53(4): 1085–1091.

|

Tian H L, Zhao J Y, Zhang H Y, et al. 2015. Bacterial community shift along with the changes in operational conditions in a membrane-aerated biofilm reactor[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 99(7): 3279–3290.

DOI:10.1007/s00253-014-6204-7

|

Vieno N, Sillanpaa M. 2014. Fate of diclofenac in municipal wastewater treatment plant-A review[J]. Environment International, 69: 28–39.

DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2014.03.021

|

Wang X C, Shen J M, Chen Z L, et al. 2016a. Removal of pharmaceuticals from synthetic wastewater in an aerobic granular sludge membrane bioreactor and determination of the bioreactor microbial diversity[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 100(18): 8213–8223.

DOI:10.1007/s00253-016-7577-6

|

Wang Z, Gao M, She Z, et al. 2015. Effects of hexavalent chromium on performance and microbial community of an aerobic granular sequencing batch reactor[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(6): 4575–4586.

DOI:10.1007/s11356-014-3704-z

|

Wang Z, Gao M, Wei J, et al. 2016b. Extracellular polymeric substances, microbial activity and microbial community of biofilm and suspended sludge at different divalent cadmium concentrations[J]. Bioresource Technology, 205: 213–221.

DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.01.067

|

温智皓, 段艳平, 孟祥周, 等. 2013. 城市污水处理厂及其受纳水体中5种典型PPCPs的赋存特征和生态风险[J]. 环境科学, 2013, 34(3): 927–932.

|

Xue W, Wu C, Xiao K, et al. 2010. Elimination and fate of selected micro-organic pollutants in a full-scale anaerobic/anoxic/aerobic process combined with membrane bioreactor for municipal wastewater reclamation[J]. Water Research, 44(20): 5999–6010.

DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2010.07.052

|

游偲.2012.海洋异养细菌对溢油污染响应特征的初步研究[D].青岛: 中国海洋大学.30-32

http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10423-1012505139.htm |

Zhang D, Luo J, Lee Z M, et al. 2016a. Characterization of microbial communities in wetland mesocosms receiving caffeine-enriched wastewater[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(14): 14526–14539.

DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-6586-4

|

Zhang T, Shao M F, Ye L. 2012. 454 pyrosequencing reveals bacterial diversity of activated sludge from 14 sewage treatment plants[J]. Isme Journal, 6(6): 1137–1147.

DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.188

|

Zhang Y, Geng J, Ma H, et al. 2016b. Characterization of microbial community and antibiotic resistance genes in activated sludge under tetracycline and sulfamethoxazole selection pressure[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 571: 479–486.

DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.014

|

Zhang Y, Sun Q, Zhou J, et al. 2015. Reduction in toxicity of wastewater from three wastewater treatment plants to alga (Scenedesmus obliquus) in northeast China[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 119: 132–139.

DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.04.034

|

Zhao Y, Feng Y, Li J, et al. 2018. Insight into the aggregation capacity of anammox consortia during reactor start-up[J]. Environment Science & Technology, 52(6): 3685–3695.

|

Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Ren H Q, et al. 2015. Physicochemical characteristics and microbial community evolution of biofilms during the start-up period in a moving bed biofilm reactor[J]. Bioresource Technology, 180: 345–351.

DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.006

|

2019, Vol. 39

2019, Vol. 39