2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049

脱卤球菌纲(Dehalococcoidia class, 简写为Dia)是绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi phylum)下属八大纲之一(Dehalococcoidia、Anaerolineae、Caldilineae、Ktedonobacteria、Thermomicrobia、Chloroflexia、Ardenticatenia和Thermoflexia)(Kawaichi et al., 2013; Dodsworth et al., 2014; Hanada, 2014).脱卤球菌纲含有已正式命名的脱卤拟球菌Dehalococcoides(Dhc)、脱卤单胞菌Dehalogenimonas(Dhgm)及尚未正式命名的Candidatus “Dehalobium”.来自这3个属的细菌均是严格厌氧的专一性有机卤化物呼吸微生物, 并且只能利用氢气或甲酸盐作为电子供体来裂解有机卤化物的碳-卤素键, 并从中获得能量来供给自身的新陈代谢活动.对脱卤拟球菌(Dhc)和脱卤单胞菌(Dhgm)微生物的关注, 主要来源于清理有机氯化物污染场地(如四氯乙烯、三氯乙烯)的实际需求, 而对于脱卤球菌纲微生物在自然环境中的生态作用还缺乏足够深入的研究(Adrian et al., 2016).

1.2 脱卤拟球菌属Freedman和Gossett从下水道污泥中取样, 首次富集培养了能将四氯乙烯(Tetrachloroethene)和三氯乙烯(Trichloroethene)还原降解为一氯乙烯和乙烯的厌氧菌群(Freedman et al., 1989).在富集培养过程中, 研究者采取了一系列手段来优化脱氯微生物的培养条件, 比如在培养瓶中加入氢气作为脱氯的直接电子供体, 添加经过灭菌、离心和过滤后的污泥上清液, 以及添加维生素B12和碳源乙酸钠(Hungate, 1969).Maymo-Gatell等对Freedman和Gossett富集的脱氯菌群开展了分离和纯化研究, 利用脱氯微生物对抑制细菌肽聚糖合成的抗生素有抗逆这一特点, 在培养基中加入抗生素(如100 mg·L-1万古霉素或高达3 g·L-1氨苄青霉素)来抑制非目标微生物生长, 最终成功分离出脱卤拟球菌195菌株(DiStefano et al., 1991; Maymó-Gatell et al., 1997).脱卤拟球菌195菌株属绿弯菌门, 呈圆盘状, 细胞体积约为0.02 μm3, 比大肠杆菌细胞小约30倍;且该菌株缺乏肽聚糖细胞壁, 但拥有类似于古细菌的S层蛋白亚基结构的细胞膜, 这也解释了195菌株对万古霉素和氨苄青霉素等抗生素有抗性的原因.此外, 195菌株是一株只能利用氢气作为唯一电子供体、有机卤化物作为电子受体的严格厌氧菌.目前没有发现该菌株还能利用非有机卤化物作为电子受体(如硝酸根、硫酸根、三价铁离子、延胡索酸).

在随后的十几年又有新的脱卤拟球菌菌株不断被鉴定和分离出来, 这些不同的脱卤拟球菌菌株能利用多种不同的脂肪族和芳香族卤代化合物作为电子受体.例如, 研究人员从美国密歇根州受氯乙烯污染的Bachman Road污染场地分离出了脱卤拟球菌BAV1菌株, 该菌株是在含有丙酮酸、氢气和一氯乙烯的液体培养基中富集培养, 并用氨苄青霉素在10-7稀释度下分离出来;除了一氯乙烯, 菌株BAV1还可以利用二氯乙烯(Dichloroethenes)3种异构体及1, 2-二氯乙烷和乙烯基溴作为电子受体(He et al., 2003a;2003b).Adrian等(2000)分离出了CBDB1菌株, 该菌株可降解多氯苯和其他氯代芳香族化合物(二英、多氯和多氯联苯等).虽然最初报道CBDB1菌株不能使用氯乙烯, 但后续研究表明该菌株可将四氯乙烯和三氯乙烯降解脱氯至反式和顺式二氯乙烯(Marco-Urrea et al., 2011).Muller等(2004)从德克萨斯州维多利亚市含苯甲酸盐和三氯乙烯的污染场地取样, 以一氯乙烯作为电子受体富集培养了VS菌株, 该菌株可降解顺式二氯乙烯和1, 1-二氯乙烯.Rosner等(1997)从美国密歇根州红雪松河原始环境沉积物中分离出了FL2菌株.2013年, Löffler等正式命名脱卤拟球菌属并将上述菌株都归入该属下面的Dehalococcoides mccartyi种(Löffler et al., 2013).

1.3 脱卤单胞菌属脱卤单胞菌Dehalogenimonas属是新近发现的另一类专一性厌氧脱卤细菌, 其成员同脱卤拟球菌一样只能通过呼吸有机卤化物(如1, 2-二氯乙烷、1, 2-二氯丙烷、1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷、1, 1, 2, 2-四氯乙烷、1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷)产生能量来供给生长繁殖.目前, 脱卤单胞菌属包含3个已正式命名的种:Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens(Yan et al., 2009)、Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens(Bowman et al., 2013)和Dehalogenimonas formicexedens(Key et al., 2017), 以及尚未正式命名的种(Candidatus “Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” (Yang et al., 2017)).这3个已正式命名种的模式菌株均是从美国路易斯安那州巴吞鲁日市附近的一个受到高浓度氯代烷烃和氯代烯烃污染的超级基金场地(Superfund Site)的地下水中分离出来.脱卤单胞菌属的菌株具有相同或高度类似特征.例如, 它们都是严格厌氧的有机卤呼吸细菌, 细胞生长耦联还原性脱卤反应, 细胞尺寸相对较小(直径约为0.3~1.1 μm), 不能形成孢子, 革兰氏阴性, 最适生长温度约为30 ℃, 无运动特征的不规则球形菌, 并且耐受一定浓度的氨苄青霉素(1.0 g·L-1)和万古霉素(0.1 g·L-1)等抗生素(Yan et al., 2009; Bowman et al., 2013; Key et al., 2017).其次, 在有机卤化物降解途径和机制方面, 脱卤单胞菌菌株能够从相邻碳原子同时除去两个卤素并形成C═C双键, 例如, 通过一步脱氯反应将1, 2-二氯乙烷(1, 2-Dichloroethane)和1, 2-二氯丙烷(1, 2-Dichloropropane)分别转化为无毒的终产物乙烯和丙烯.然而, 这些菌株不能利用仅含有一个氯取代基的脂族烷烃(如1-氯丙烷, 2-氯丙烷), 以及一个碳原子上有多个氯取代基的脂族烷烃(如1, 1-二氯乙烷、1, 1, 1-三氯乙烷、二氯甲烷、三氯甲烷、四氯化碳)、氯化苯(1-氯苯、1, 2-二氯苯)或氯代烯烃(如四氯噻吩、三氯乙烯、顺式1, 2-二氯乙烯、反式-1, 2-二氯乙烯、氯乙烯)(Yan et al., 2009; Bowman et al., 2013; Key et al., 2017).与脱卤拟球菌属菌株不同的是, 除氢气外甲酸盐也可作为脱卤单胞菌生长的直接电子供体.在无氢气或甲酸盐情况下, 乙酸盐、丁酸盐、柠檬酸盐、乙醇、果糖、富马酸盐、葡萄糖、乳酸盐、乳糖、苹果酸盐、甲醇、甲乙酮、丙酸盐、丙酮酸盐、琥珀酸盐或酵母提取物无法单独支持脱卤单胞菌生长.

2 脱卤拟球菌属与脱卤单胞菌属基因组(Genomes of Dehalococcoides and Dehalogenimonas genera)脱卤拟球菌和脱卤单胞菌基因组上编码的大部分管家基因(Housekeeping genes)都只有单拷贝, 并且它们的基因组中缺失一些属于细菌的常见功能基因, 如肽聚糖合成、运动和环境适应性基因.分析脱卤单胞菌和脱卤拟球菌全基因组序列, 有助于揭示有机卤化物呼吸细菌(Organohalide-respiring bacteria, OHRB)的生理和进化特征.脱卤拟球菌不同菌株的核心基因组序列高度保守, 包含1029~1118个基因, 占各菌株总基因数的63%~77%(McMurdie et al., 2009), 不同菌株间的基因组区别主要存在于位于复制起点两侧的“可塑性区域”(Kube et al., 2005; McMurdie et al., 2009).这个“可塑性区域”是区别脱卤单胞菌和脱卤拟球菌对于不同有机卤化物利用能力的特征区域(West et al., 2008).

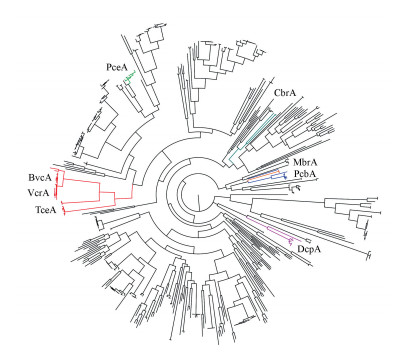

脱卤拟球菌和脱卤单胞菌基因组高度精简, 长度从1.34~2.0 Mb不等, 通常含有10~36个还原性脱卤酶基因.目前所有已经被生化鉴定的还原性脱卤酶基因都编码一个双精氨酸跨膜易位(TAT)信号序列, 以及两个Fe-S簇结合结构域和一个类咕啉辅助因子结合结构域(Yi et al., 2012).还原性脱卤酶基因簇主要包括rdhA和rdhB两个基因, 其中, rdhA基因编码还原性脱卤酶用于催化碳—卤键断裂反应;rdhB基因编码一种小的细胞膜锚蛋白, 起到将还原性脱卤酶固定到细胞膜的作用.与这些还原性脱卤酶基因相邻的开放阅读框(Open Reading Frame, ORF)大多数被注释为具有转录控制作用, 表明脱卤拟球菌和脱卤单胞菌利用有机卤化物进行能量代谢受到一定的调控.此外, 脱卤拟球菌和脱卤单胞菌基因组中绝大多数还原性脱卤酶基因的功能尚未被阐明(图 1), 因此, 还需进一步研究来揭示这些还原性脱卤酶的具体功能和底物范围.随着测序技术的不断发展, 还原性脱卤酶同源序列被不断发现, 但仍缺乏对于脱卤酶序列多样性与其功能之间相关性的深入研究.

|

| 图 1 Uniprot蛋白质数据库中所有属于脱卤球菌纲微生物的还原脱卤酶进化树 (只有极少部分的还原脱卤酶功能已被阐明, 而大部分的还原脱卤酶功能则未知;BvcA和VcrA为一氯乙烯脱卤酶, TceA为三氯乙烯脱卤酶, PceA和MbrA为四氯乙烯脱卤酶, CbrA为氯代苯脱卤酶, PcbA为多氯联苯脱卤酶, DcpA为1, 2-二氯丙烷脱卤酶) Fig. 1 Phylogenetic tree of reductive dehalogenases of Dehalococcodia microorganisms retrieved from UniProt database |

脱卤拟球菌这类普遍存在于自然环境中的脱氯菌并不是在所有四氯乙烯或者三氯乙烯污染场地中都能被检测到.脱卤拟球菌的缺失往往会导致四氯乙烯的降解产物(如二氯乙烯和一氯乙烯)的原位积累, 而通过添加含脱卤拟球菌的微生物菌剂则成为解决二氯乙烯和一氯乙烯积累问题的一种有效手段, 从而达到氯乙烯类污染产地无毒化和彻底修复的目的.脱卤拟球菌菌剂的商业化开发及利用脱卤拟球菌生物菌剂进行场地修复的案例已有一些报道(Stroo et al., 2012).Chen等(2014)利用定量荧光PCR(qPCR)的方法发现, 在向污染场地注入发酵底物(农用饲料级糖蜜)和碱度(碳酸氢钠)后, 污染物场地里脱卤单胞菌16S rRNA基因拷贝增加了100多倍, 同时发现1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷和1, 2-二氯乙烷的浓度在减少, 表明了脱卤单胞菌在原位修复卤代脂肪族污染物中的重要作用.因此, 脱卤单胞菌和脱卤拟球菌在有机氯污染物降解及污染物场地修复中均有着不可忽视的重要作用(Yang et al., 2017).

4 自然环境中脱卤球菌纲微生物(Dehalococcoidia in the natural environments)随着新一代高通量测序技术的不断成熟, 以及单细胞测序技术的快速发展和测序价格的不断降低, 测序技术被广泛应用于探究原始环境(如海底沉积物、地下水、湖底水样等)中微生物群落的组成成分和生态功能.在Integrated Microbial Genomes & Microbiomes(IMG/MER)数据库中(https://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/mer/main.cgi)收录了131个脱卤球菌纲的基因组(Chen et al., 2019).其中, 有20多个脱卤单胞菌或脱卤拟球菌属的基因组来源于陆地原生或污染环境, 其它111个脱卤球菌纲微生物基因组是从海洋环境样品中利用单细胞测序技术或宏基因组-组装基因组技术拼装得到.系统进化树分析进一步表明, 海洋环境与陆地环境中脱卤球菌纲微生物分属于不同的群集, 而这种差异性则可能是由于这些脱卤微生物受到不同环境因子(如卤代有机物种类、地质化学条件、维生素B12的存在与否)的影响所致.

在胡安德富卡山脊东侧深部沉积物中, 研究人员发现60.3%~86.7%的细菌16S rRNA基因可以被归为绿弯菌门, 而绿弯菌门中有50%的细菌16S rRNA基因又可以被归入脱卤球菌纲(Labonte et al., 2017).Kaster和Wasmund分别利用单细胞测序技术分析了海底沉积物中脱卤球菌纲细菌的基因组, 发现这些脱卤球菌纲细菌(如Dsc1、Dsc2和DEH-J10)的基因组中并没有还原性脱卤酶基因的存在, 意味着这些自然环境中尚未被分离培养的脱卤球菌纲细菌也许不能利用有机卤呼吸作为能量供给自身生命活动代谢(Kaster et al., 2014; Wasmund et al., 2014;2015).在DEH-J10和Dsc2这两个基因组草图中, 均发现了卤代酸脱卤酶(Haloacid dehalogenase)(Kaster et al., 2014; Wasmund et al., 2014;2015), 说明某些脱卤球菌纲微生物.虽然不能进行还原性脱卤, 但可能通过卤代酸脱卤酶的功能参与卤素循环, 脱去卤素后的有机酸可以作为碳源或能源供其他微生物生长.在另一项单细胞测序研究中, 研究人员在一株名为DEH-C11的脱卤球菌纲微生物基因组中发现了能够进行亚硫酸根离子还原的功能性基因(Sulfite reductase), 这也是首次发现绿弯菌门的微生物可能参与到硫元素循环(Wasmund et al., 2016).但需要注意的是, 单细胞测序的脱卤球菌纲细菌的基因组只有不到80%的完整性, 而且这些单细胞测序的基因组仅进行了生物信息学研究, 大部分的ORFs的功能还未得到生化实验验证.因此, 这些尚未被分离培养的脱卤球菌纲细菌是否可以进行有机卤化物呼吸或者降解有机卤化物还需要进一步的实验研究.虽然在各种深海沉积物样品中利用PCR等分子生物学工具检测到了还原性脱卤酶的存在(Futagami et al., 2009; Teske, 2013; Kawai et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2018), 并且通过对脱卤球菌纲微生物的基因组分析也发现了还原性脱卤酶, 但海底沉积物中脱卤球菌纲是否参与到降解天然卤代有机化合物中仍需要进一步的实验研究.

Krzmarzick等(2012)对来自美国8个州立公园和1个国家森林保护区的116个未受污染的陆地土壤样品进行了调查, 在103个样品中检测到了类似于脱卤拟球菌的脱卤球菌纲微生物.虽然这类微生物的功能大部分仍然未知, 但研究者发现类似脱卤拟球菌的脱卤球菌纲微生物数量同有机氯与总有机碳的比值呈正相关, 研究认为这类能进行有机卤化物呼吸的脱卤球菌纲细菌很有可能在生物地球化学卤素循环中发挥着重要作用(如从有机卤化合物中释放氯和溴等卤族元素).此外, 他们还利用分子生物学方法和工具分析了68个从湖泊沉积物中收集的样品, 在67个样品中都检测到了可能进行有机卤化物呼吸的脱卤球菌纲微生物(Krzmarzick et al., 2013).又有研究者通过高通量测序技术在北极某盐湖60 m深处的缺氧水体中, 以及世界上最深和最宽阔的湖泊—贝加尔湖的光层(0~25 m)和近底层(1465~1515 m)中均检测到了脱卤单胞菌的存在(Comeau et al., 2012; Kurilkina et al., 2016).但对于脱卤单胞菌在这些环境中的生态功能仍然所知甚少.

5 脱卤球菌纲微生物的生态功能(Ecological roles of Dehalococcoidia) 5.1 脱卤球菌纲微生物与其他微生物的相互作用脱卤球菌纲包含能进行严格厌氧有机卤呼吸的微生物, 与其它厌氧微生物有着重要的联系.在厌氧环境中, 与碳、氮、硫、铁、锰和卤族元素相关的还原细菌(如硫酸还原菌、异养铁还原菌、硝酸还原菌、卤代有机物还原菌)都需要利用氢气或其他物质作为电子供体, 而电子供体的竞争会导致不同还原细菌在微生物群落中占据不同的生态位(图 2).有研究报道, 脱卤球菌纲微生物驱动的有机卤呼吸过程可能耦合甲烷厌氧氧化(Anaerobic Methane Oxidation)或者乙酸厌氧氧化过程, 其内在机制在于甲烷厌氧氧化或乙酸厌氧氧化产生的氢气能够作为电子供体供给脱卤球菌纲微生物进行能量代谢活动.这种可能的共生现象已经在一些海洋环境中被发现, 如南极弗里克塞尔湖(Saxton et al., 2016)和韩国东海郁陵岛盆地的含甲烷水合物的沉积物样品中(Lee et al., 2016).

|

| 图 2 不同元素循环之间基于氢气或电子竞争与供给的相互作用 (灰线代表还原过程, 黑线代表氧化过程;SRB/A代表硫酸盐还原细菌或古菌, SOB/A代表硫氧化细菌或古菌, IRB/A代表铁还原细菌或古菌, MnRB/A代表锰还原细菌或古菌, IOB/A代表铁氧化细菌或古菌, MnOB/A代表锰氧化细菌或古菌, NFB/A代表固氮细菌或古菌, AOB/A代表氨氧化细菌或古菌, NRB/A代表硝酸盐还原细菌或古菌, NOB/A代表亚硝酸根氧化细菌或古菌) Fig. 2 Interactions among different elements cycling based on supply and demand of hydrogen or electron |

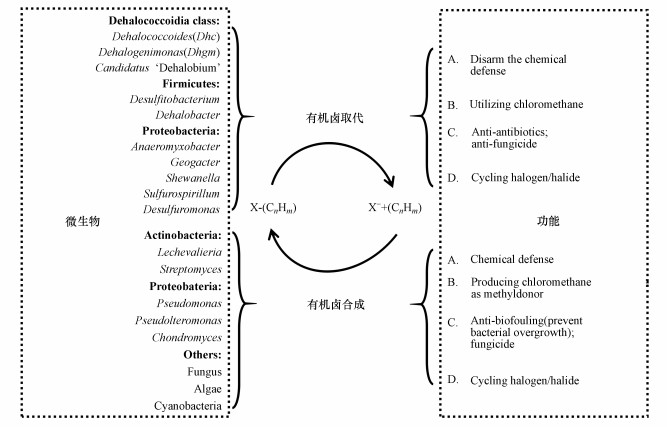

抗生素是微生物所产生的具有抗病原体或其他活性的一类次级代谢产物, 能干扰其他细胞的正常代谢功能(Wright et al., 2013).目前已知天然抗生素不下万种, 常用抗生素中有许多都是氯化或卤化有机物, 如三氯生、氯霉素、金霉素、灰黄霉素和万古霉素等(Winterton, 2000), 其中的卤取代基团决定了这些类型抗生素的生物活性.关于抗生素到底是一种“化学武器”用来抑制和杀死其他微生物, 还是不同微生物之间进行交流的“信号分子”的争论一直在持续(Linares et al., 2006; Fajardo et al., 2008; Andersson et al., 2014; Abrudan et al., 2015; Townsley et al., 2017; Westhoff et al., 2017).因为抗生素的抑菌或杀菌作用, 人们常将其作为抗菌剂来抑制杂菌生长, 但对于脱卤球菌纲中的脱卤单胞菌和脱卤拟球菌来说却不是这样.由于脱卤单胞菌和脱卤拟球菌具有脱卤转化一些卤代抗生素继而使其丧失生物活性的潜力, 这些脱卤球菌纲中的有机卤呼吸细菌在自然环境中的潜在生态作用值得关注.例如, 一些海洋生物能合成氯代抗生素来抑制微生物在体内或体表的生长, 脱卤球菌纲微生物则可能利用还原脱卤酶来转化这些氯代抗生素, 从而解除这些能产生卤代抗生素生物的化学防御系统(图 3).有实验表明, 当向含有脱卤球菌纲微生物的混合菌群添加三氯生时, 脱卤球菌纲微生物得到高度富集, 很有可能是因为脱卤球菌纲微生物利用三氯生作为电子受体供给自身的能量代谢活动从而间接达到降解三氯生的目的(McNamara et al., 2013).脱卤球菌纲微生物能够降解抗生素的能力(图 3), 使其作为一种抗-抗生素微生物在自然界发挥了独特的生态作用, 而这种猜测需要更多的实验去证实.

|

| 图 3 参与有机卤化物循环的微生物及其功能 Fig. 3 Microorganisms involved in organohalogens cycling and their functions |

经过近30年的研究, 存在于自然环境中的脱卤球菌纲微生物的生理学、生物化学和生态学问题仍有许多没有得到解答(Wasmund et al., 2015).例如, 脱卤球菌纲细菌在陆地和水生(淡水和海洋)生态环境中的作用仍是未知的(Adrian et al., 2016).随着化学分析技术的不断进步, 天然产物中的有机卤化物被检测和识别的数量不断增加, 迄今为止已报道了超过5000种天然有机卤化物, 其中包括约2200种天然有机氯化物(Gribble, 2010;Adrian et al., 2016).这些天然产物中的卤族元素很有可能通过脱卤球菌纲微生物的代谢作用被释放出来, 从而进入卤族元素的生物地球化学循环(图 3).相较于碳、氮、硫或者铁元素的生物地球化学循环研究已有很多报道, 对于脱卤微生物介导下的卤族元素循环的研究却较少.研究脱卤球菌纲微生物对卤族循环的作用, 将有助于阐明各种元素生物地球化学循环之间的相互关系(图 2~3)(Oberg, 2002).

6 研究展望(Future research)本文旨在强调脱卤球菌纲微生物在自然环境中对卤代有机物循环的作用, 但这一假设还需要进一步的跨学科研究(如地球化学、微生物学、海洋学、地质学、化学)来验证.关于脱卤球菌纲微生物, 还有如下问题有待进一步调查研究.

1) 脱卤球菌纲微生物普遍于存在海洋环境中, 但迄今为止人们无法从海洋环境中培养和分离出脱卤球菌纲微生物.研究开发不同的厌氧微生物技术, 用于脱卤球菌纲微生物的富集培养, 将会帮助人们更好地认识脱卤球菌纲微生物在海洋环境中的生态作用.

2) 脱卤球菌纲微生物中大部分还原性脱卤酶仍未得到生化鉴定, 从而限制了人们对其生理生态功能的解读.为了阐明还原性脱卤素酶的底物范围及功能, 还需开发一套适合脱卤球菌纲微生物的生化、遗传及分子生物学工具.

3) 虽然(卤代)抗生素是“化学武器”还是“信号分子”的争论仍未得到解决, 但不可否认的是(卤代)抗生素在微生物群落结构中发挥着重要作用.脱卤球菌纲微生物作为一种抗-抗生素微生物, 通过转化卤代抗生素来影响微生物群落结构与功能的过程是值得进一步研究的问题.

4) 有机卤化合物既是自然界也是人类社会生产活动的产物, 脱卤球菌纲微生物与有机卤化物的降解转化密切相关.对于脱卤球菌纲微生物的生理生态功能的研究, 不仅有助于人们开展有机氯污染场地清理及修复, 也将拓展对于卤素循环与其他元素循环之间的相互作用关系, 以及对地球气候环境变化影响的理解.

Abrudan M I, Smakman F, Grimbergen A J, et al. 2015. Socially mediated induction and suppression of antibiosis during bacterial coexistence[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(35): 11054–11059.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1504076112

|

Adrian L, Szewzyk U, Wecke J, et al. 2000. Bacterial dehalorespiration with chlorinated benzenes[J]. Nature, 408: 580–583.

DOI:10.1038/35046063

|

Adrian L, Löffler F E. 2016. Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria[M]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

|

Andersson D I, Hughes D. 2014. Microbiological effects of sublethal levels of antibiotics[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 12: 465–478.

DOI:10.1038/nrmicro3270

|

Bowman K S, Nobre M F, da Costa M S, et al. 2013. Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens sp. nov., a chlorinated-alkane-dehalogenating bacterium isolated from groundwater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 63: 1492–1498.

DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.045054-0

|

Chen I A, Chu K, Palaniappan K, et al. 2019. IMG/M v.5.0:an integrated data management and comparative analysis system for microbial genomes and microbiomes[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 47: 666–677.

DOI:10.1093/nar/gky1119

|

Chen J, Bowman K S, Rainey F A, et al. 2014. Reassessment of PCR primers targeting 16S rRNA genes of the organohalide-respiring genus Dehalogenimonas[J]. Biodegradation, 25(5): 747–756.

DOI:10.1007/s10532-014-9696-z

|

Comeau A M, Harding T, Galand P E, et al. 2012. Vertical distribution of microbial communities in a perennially stratified Arctic lake with saline, anoxic bottom waters[J]. Scientific Reports, 2: 604.

DOI:10.1038/srep00604

|

DiStefano T D, Gossett J M, Zinder S H. 1991. Reductive dechlorination of high concentrations of tetrachloroethene to ethene by an anaerobic enrichment culture in the absence of methanogenesis[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 57(8): 2287–2292.

|

Dodsworth J A, Gevorkian J, Despujos F, et al. 2014. Thermoflexus hugenholtzii gen.nov., sp.nov., a thermophilic, microaerophilic, filamentous bacterium representing a novel class in the Chloroflexi, Thermoflexia classis nov., and description of Thermoflexaceae fam.nov. and Thermoflexales ord.nov[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 64: 2119–2127.

DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.055855-0

|

Fajardo A, Martinez J L. 2008. Antibiotics as signals that trigger specific bacterial responses[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 11(2): 161–167.

DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.006

|

Freedman D L, Gossett J M. 1989. Biological reductive dechlorination of tetrachloroethylene and trichloroethylene to ethylene under methanogenic conditions[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 55(9): 2144–2151.

|

Futagami T, Morono Y, Terada T, et al. 2009. Dehalogenation activities and distribution of reductive dehalogenase homologous genes in marine subsurface sediments[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 75(21): 6905–6909.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.01124-09

|

Gribble G W. 2010. Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds:A Comprehensive Update[M]. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

|

Hanada S.2014.The phylum Chloroflexi, the Family Chloroflexaceae, and the Related Phototrophic Families Oscillochloridaceae and Roseiflexaceae//Rosenberg E, DeLong E F, Lory S, et al.The Prokaryotes[M]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.515-532

|

He J Z, Ritalahti K M, Aiello M R, et al. 2003a. Complete detoxification of vinyl chloride by an anaerobic enrichment culture and identification of the reductively dechlorinating population as a Dehalococcoides species[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 69(2): 996–1003.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.2.996-1003.2003

|

He J Z, Ritalahti K M, Yang K L, et al. 2003b. Detoxification of vinyl chloride to ethene coupled to growth of an anaerobic bacterium[J]. Nature, 424(6944): 62–65.

DOI:10.1038/nature01717

|

Hungate R.1969.A Roll Tube Method for Cultivation of Strict Anaerobes//Morrris J R, Ribbons D W. Methods in Microbiology[M]. London: Academic Press.117-132

|

Kaster A K, Mayer-Blackwell K, Pasarelli B, et al. 2014. Single cell genomic study of Dehalococcoidetes species from deep-sea sediments of the Peruvian Margin[J]. ISME Journal, 8: 1831–1842.

DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.24

|

Kawai M, Futagami T, Toyoda A, et al. 2014. High frequency of phylogenetically diverse reductive dehalogenase-homologous genes in deep subseafloor sedimentary metagenomes[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5: 80.

|

Kawaichi S, Ito N, Kamikawa R, et al. 2013. Kawaichi S, Ito N, Kamikawa R, et al.2013.Ardenticatena maritima gen.nov., sp.nov., a ferric iron- and nitrate-reducing bacterium of the phylum 'Chloroflexi' isolated from an iron-rich coastal hydrothermal field, and description of Ardenticatenia classis nov[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 63: 2992–3002.

DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.046532-0

|

Key T A, Bowman K S, Lee I, et al. 2017. Dehalogenimonas formicexedens sp.nov., a chlorinated alkane-respiring bacterium isolated from contaminated groundwater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 67: 1366–1373.

DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001819

|

Krzmarzick M J, Crary B B, Harding J J, et al. 2012. Natural niche for organohalide-respiring Chloroflexi[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(2): 393–401.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.06510-11

|

Krzmarzick M J, McNamara P J, Crary B B, et al. 2013. Abundance and diversity of organohalide-respiring bacteria in lake sediments across a geographical sulfur gradient[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 84(2): 248–258.

DOI:10.1111/1574-6941.12059

|

Kube M, Beck A, Zinder S H, et al. 2005. Genome sequence of the chlorinated compound-respiring bacterium Dehalococcoides species strain CBDB1[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 23: 1269–1273.

DOI:10.1038/nbt1131

|

Kurilkina M I, Zakharova Y R, Galachyants Y P, et al. 2016. Bacterial community composition in the water column of the deepest freshwater Lake Baikal as determined by next-generation sequencing[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology.

DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiw094

|

Labonte J M, Lever M A, Edwards K J, et al. 2017. Influence of igneous basement on deep sediment microbial diversity on the eastern Juan de Fuca ridge flank[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8: 1434.

DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01434

|

Lee J W, Kwon K K, Bahk J J, et al. 2016. Metagenomic analysis reveals the contribution of anaerobic methanotroph-1b in the oxidation of methane at the Ulleung Basin, East Sea of Korea[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 54(12): 814–822.

DOI:10.1007/s12275-016-6379-y

|

Linares J F, Gustafsson I, Baquero F, et al. 2006. Antibiotics as intermicrobial signaling agents instead of weapons[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(51): 19484–19489.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0608949103

|

Löffler F E, Yan J, Ritalahti K M, et al. 2013. Dehalococcoides mccartyi gen.nov., sp.nov., obligately organohalide-respiring anaerobic bacteria relevant to halogen cycling and bioremediation, belong to a novel bacterial class, Dehalococcoidia classis nov., order Dehalococcoidales ord.nov. and family Dehalococcoidaceae fam.nov., within the phylum Chloroflexi[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 63: 625–635.

DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.034926-0

|

Marco-Urrea E, Nijenhuis I, Adrian L. 2011. Transformation and carbon isotope fractionation of tetra- and trichloroethene to trans-dichloroethene by Dehalococcoides sp.strain CBDB1[J]. Environmental science & technology, 45(4): 1555–1562.

|

Marshall I P G, Karst S M, Nielsen P H, et al. 2018. Metagenomes from deep Baltic Sea sediments reveal how past and present environmental conditions determine microbial community composition[J]. Marine Genomics, 37: 58–68.

DOI:10.1016/j.margen.2017.08.004

|

Maymó-Gatell X, Chien Y T, Gossett J M, et al. 1997. Isolation of a bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetrachloroethene to ethene[J]. Science, 276(5318): 1568–1571.

DOI:10.1126/science.276.5318.1568

|

McMurdie P J, Behrens S F, Muller J A, et al. 2009. Localized plasticity in the streamlined genomes of vinyl chloride respiring Dehalococcoides[J]. PLoS Genetics, 5: e1000714.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000714

|

McNamara P J, Krzmarzick M J. 2013. Triclosan enriches for Dehalococcoides-like Chloroflexi in anaerobic soil at environmentally relevant concentrations[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 344(1): 48–52.

DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12153

|

Muller J A, Rosner B M, Von Abendroth G, et al. 2004. Molecular identification of the catabolic vinyl chloride reductase from Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS and its environmental distribution[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 70(8): 4880–4888.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.70.8.4880-4888.2004

|

Oberg G. 2002. The natural chlorine cycle-fitting the scattered pieces[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 58(5): 565–581.

DOI:10.1007/s00253-001-0895-2

|

Rosner B M, McCarty P L, Spormann A M. 1997. In vitro studies on reductive vinyl chloride dehalogenation by an anaerobic mixed culture[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 63(11): 4139–4144.

|

Saxton M A, Samarkin V A, Schutte C A, et al. 2016. Biogeochemical and 16S rRNA gene sequence evidence supports a novel mode of anaerobic methanotrophy in permanently ice-covered Lake Fryxell, Antarctica[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 61: S119–S130.

DOI:10.1002/lno.10320

|

Stroo H F, Leeson A, Ward C H. 2012. Bioaugmentation for Groundwater Remediation[M]. New York: Springer.

|

Teske A.2013.Marine Deep Sediment Microbial Communities//Rosenberg E, DeLong E F, Lory S, et al.The Prokaryotes[M].Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.123-138

|

Townsley L, Shank E A. 2017. Natural-product antibiotics:cues for modulating bacterial biofilm formation[J]. Trends in Microbiology, 25(12): 1016–1026.

DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2017.06.003

|

Wasmund K, Schreiber L, Lloyd K G, et al. 2014. Genome sequencing of a single cell of the widely distributed marine subsurface Dehalococcoidia, phylum Chloroflexi[J]. ISME Journal, 8(2): 383–397.

DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.143

|

Wasmund K, Algora C, Muller J, et al. 2015. Development and application of primers for the class Dehalococcoidia(phylum Chloroflexi) enables deep insights into diversity and stratification of subgroups in the marine subsurface[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 17: 3540–3556.

DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.12510

|

Wasmund K, Cooper M, Schreiber L, et al. 2016. Single-cell genome and group-specific dsrAB sequencing implicate marine members of the class Dehalococcoidia(phylum Chloroflexi) in sulfur cycling[J]. mBio, 7(3): 266–316.

|

West K A, Johnson D R, Hu P, et al. 2008. Comparative genomics of "Dehalococcoides ethenogenes" 195 and an enrichment culture containing unsequenced "Dehalococcoides" strains[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74(11): 3533–3540.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.01835-07

|

Westhoff S, van Wezel G P, Rozen D E. 2017. Distance-dependent danger responses in bacteria[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 36: 95–101.

DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2017.02.002

|

Winterton N. 2000. Chlorine:the only green element-towards a wider acceptance of its role in natural cycles[J]. Green Chemistry, 2(5): 173–225.

DOI:10.1039/b003394o

|

Wright G D, Hung D T, Helmann J D. 2013. How antibiotics kill bacteria:new models needed?[J]. Nature Medicine, 19(5): 544–545.

DOI:10.1038/nm.3198

|

Yan J, Rash B A, Rainey F A, et al. 2009. Isolation of novel bacteria within the Chloroflexi capable of reductive dechlorination of 1, 2, 3-trichloropropane[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 11: 833–843.

DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01804.x

|

Yang Y, Higgins S A, Yan J, et al. 2017. Grape pomace compost harbors organohalide-respiring Dehalogenimonas species with novel reductive dehalogenase genes[J]. ISME Journal, 11: 2767–2780.

DOI:10.1038/ismej.2017.127

|

Yi S, Seth E C, Men Y J, et al. 2012. Versatility in corrinoid salvaging and remodeling pathways supports corrinoid-dependent metabolism in Dehalococcoides mccartyi[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(21): 7745–7752.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.02150-12

|

2019, Vol. 39

2019, Vol. 39