2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心, 饮用水科学与技术重点实验室, 北京 100085

2. Key Laboratory of Drinking Water Science and Technology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085

抗生素的长期使用甚至滥用导致环境中抗生素抗性细菌(antibiotic resistant bacteria, ARB)及抗生素抗性基因(antibiotic resistance genes, ARGs)的广泛传播(Rodriguezmozaz et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; 李超等, 2016), 已对人类健康构成了潜在威胁.生活污水处理厂是抗生素的重要“汇”, 其中较高浓度的抗生素有利于ARGs进行交换和传播(Rizzo et al., 2013; Czekalski et al., 2014), 且复杂的水质条件为ARB之间的基因转移提供了有利条件(Wang et al., 2011).研究显示, 污水处理厂常规处理工艺不能有效消除ARB和ARGs, 从而导致其在出水中普遍残留(Pruden et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010; Mao et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; 李奥林等, 2018), 甚至存在某些种类的ARGs在出水中相对丰度进一步升高的现象.Makowska等调查了波兰某采用活性污泥法的污水处理厂中抗性基因的浓度, 发现污水厂出水中的四环素抗性基因(tetA、tetB和tetM)和磺胺抗性基因(sul1和sul2)的相对丰度均高于进水(Makowska et al., 2016).Li等调查发现浙江省某采用A/O工艺的污水厂出水中tetC、tetM、sul1等ARGs的相对丰度较进水增加0.5 log(Li et al., 2015).近年来, 针对常规污染物的强化去除, 我国城市污水处理厂正进行污水处理工艺升级.许多城市污水厂已由传统的A/A/O工艺变为升级A/O工艺.同时面对污水高标准处理及再生需求, 生物活性炭等深度处理工艺逐步在城市污水厂得以应用.然而, 升级污水处理工艺在实际运行中对ARGs的削减效果尚需进一步阐明.

本研究选取了北方某采用升级A/O工艺的生活污水处理厂为研究对象, 采集了沿程污水及污泥, 采用实时荧光定量PCR技术对其中4类共9种ARGs进行了定量检测, 探究了各处理工艺段中ARGs的分布与去除情况;此外, 对比了生物活性炭及紫外消毒工艺对生物处理出水中ARGs的削减效果.研究结果将为城市污水厂工艺升级改造提供一定的理论依据与参考.

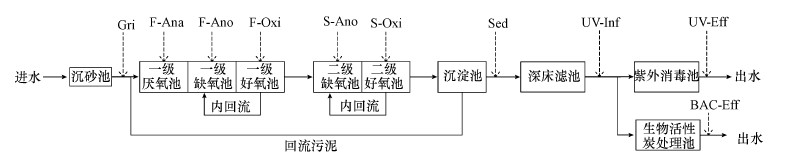

2 材料与方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 样品采集本实验采集北方某生活污水处理厂各工艺段出水及污泥进行研究, 污水厂处理规模为6.5×105 m3·d-1, 采用A/A/O+A/O工艺作为二级处理工艺, 设置紫外消毒池和生物活性炭处理池进行深度处理.处理后出水水质达到《城镇污水处理厂污染物排放标准》(DB12/599—2015) A类标准.采样时间为2019年5月, 沿污水处理流程共设置10个采样点(图 1), 分别为:沉砂池(Gri)、一级厌氧池(F-Ana)、一级缺氧池(F-Ano)、一级好氧池(F-Oxi)、二级缺氧池(S-Ano)、二级好氧池(S-Oxi)、沉淀池(Sed)、紫外线消毒池进水(UV-Inf)、紫外线消毒池出水(UV-Eff)、生物活性炭处理池出水(BAC-Eff).每个采样点均采用混合采样方式, 具体操作为一天内每间隔6 h取样, 共采集4次样品进行混合.样品于4 ℃冷藏并立即运回实验室进行后续处理.

|

| 图 1 污水处理厂工艺流程图及各工艺段采样点 Fig. 1 Flow scheme of the wastewater treatment processes with sampling locations |

污水采用真空过滤装置通过0.22 μm碳酸酯滤膜(Millipore, 美国)过滤, 将滤膜剪碎放入FastDNATM Spin Kit for Soil试剂盒(MpBio, 美国)提供的Lysing Matrix E tube中, 按照试剂盒操作手册进行污水DNA提取.各工艺段取新鲜浑浊污泥2份, 各1 mL.一份与水样相同操作, 过0.22 μm聚碳酸酯滤膜, 将滤膜剪碎, 采用FastDNATM Spin Kit for Soil试剂盒(MpBio, 美国)进行DNA提取, 获得的DNA样品保存于-20 ℃, 待测.另一份用已烘干至恒重的普通滤纸过滤, 之后将滤纸在105 ℃烘干2 h, 测定泥样干重.每个样品设置2组平行, 以减少实验误差.

2.3 ARGs的测定方法本研究采用TB Green Ⅱ实时荧光定量PCR技术对目标ARGs及16S rRNA进行定量, 目标ARGs包括3个四环素抗性基因(tetA、tetC和tetM)、2个磺胺抗性基因(sul1和sul2)、2个大环内酯抗性基因(ermA和ermF)和2个喹诺酮抗性基因(parC和gyrA)及16S rRNA, 所使用的引物及退火温度如表 1所示.

| 表 1 目标ARGs定量PCR引物序列及退火温度 Table 1 Primer sequences and annealing temperature for target ARGs of q-PCR |

用携带目标ARGs片段的质粒制作标准曲线.将各质粒用无菌水稀释成102~109 copies·μL-1的8个浓度, 按照表 2的反应体系配制反应液.采用实时荧光定量PCR技术在ABI Prism 7300系统(Applied Biosystems, 美国)上进行基因定量测定, 进样量25 μL, 反应程序为:95 ℃预变性5 min, 95 ℃变性15 s, 退火温度30 s, 72 ℃延伸30 s, 共40个循环.

| 表 2 实时荧光定量PCR反应体系 Table 2 Real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR reaction system |

各基因标准曲线相关系数R2均大于0.99, 且扩增效率为90%~ 120%, 符合PCR实验要求, 可用于各ARGs拷贝数计算.基因丰度采用绝对丰度、相对丰度两种表达方式, 分别代表目标ARGs在某种介质中的含量或目标ARGs的绝对丰度与16S rRNA的比值.

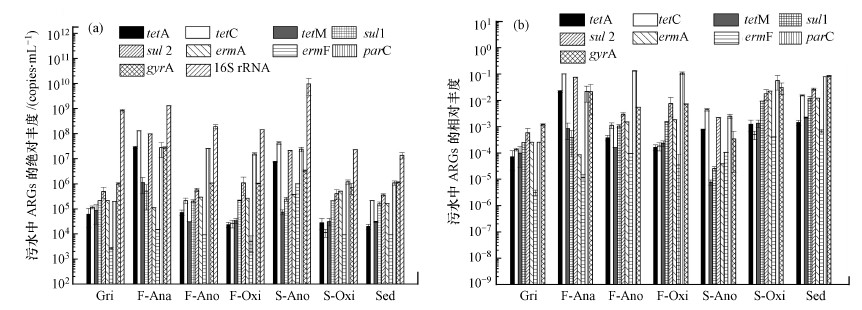

3 结果与讨论(Results and discussion) 3.1 污水中ARGs分布污水处理厂各工艺段污水中9种ARGs的绝对丰度如图 2a所示.9种目标ARGs在污水中均被检出, 其绝对丰度为2.65×103~1.70×108 copies·mL-1.四环素抗性基因中tetC在污水中的绝对丰度最高, 为2.62×104~1.31×108 copies·mL-1, 其次为tetA(1.96×104~2.87×107 copies·mL-1)和tetM(3.03×104~1.09×106 copies·mL-1).磺胺抗性基因sul1的绝对丰度(1.60×105 ~5.04×105 copies·mL-1)普遍低于sul2(3.60×105~2.14×107 copies·mL-1);喹诺酮抗性基因普遍处于较高的水平, parC和gyrA的绝对丰度分别为3.03×104~1.09×106 copies·mL-1和3.03×104~1.09×106 copies·mL-1.Makowska等调查了波兰某污水处理厂中抗性基因的丰度情况, 发现污水中tetA和tetM的绝对丰度为1.0×103 ~ 1.6×103 copies·mL-1, sul1和sul2的绝对丰度为5.4×103~1.6×105 copies·mL-1(Makowska et al., 2016), 与本研究结果相比绝对丰度较低.Zhang等在位于香港、上海和加州湾等地的污水处理厂中, 检测发现污水厂出水中tet C和tet A基因的绝对丰度为104~105 copies·mL-1(Zhang et al., 2009), 与本研究结果相近.

|

| 图 2 各工艺段污水中ARGs的绝对丰度(a)和相对丰度(b) Fig. 2 Absolute abundance (a) and relative abundance(b) of ARGs in sewage samples of each process |

沿污水处理流程来看, 沉砂池(Gri)出水中, gyrA绝对丰度最高(1.01×106 copies·mL-1), sul2次之(4.95×105 copies·mL-1), ermF最低(2.65×103 copies·mL-1).进入一级厌氧池(F-Ana)后, 各目标ARGs绝对丰度均有增加.其中, tetA、tetC和sul2增长约3 logs, ermF增长约1 log.目标ARGs丰度在一级缺氧池(F-Ano)和一级好氧池(F-Oxi)中呈逐级下降趋势.在二级缺氧池(S-Ano)中, 目标ARGs丰度增加至7.37×104~4.27×107 copies·mL-1, 而在二级好氧池(S-Oxi)中, 目标ARGs丰度下降至9.22×103~1.09×106 copies·mL-1, 最终在沉淀池(Sed)出水中, ARGs绝对丰度为103 ~ 108 copies·mL-1, 与沉砂池(Gri)出水绝对丰度相当.总体看来, 升级A/O工艺未能有效削减污水中的ARGs, 厌氧工艺环节导致ARGs的丰度增加.对16S rRNA的检测结果显示, 其在沉砂池(Gri)、一级厌氧池(F-Ana)和二级缺氧池(S-Ano)中的丰度分别为8.49 × 108、1.29× 109和9.61× 109 copies·mL-1, 因此厌氧与缺氧环节中的生物量上涨可能是导致ARGs丰度上升的重要原因.Du等在某制药废水处理厂生物处理流程中也发现类似现象, tetG丰度由进水中的102.37 copies·mL-1增加至厌氧环节中的102.97 copies·mL-1, tetX、intI1和sul1也表现出与tetG类似的趋势(Du et al., 2014).

污水处理厂各工艺段污水中9种ARGs的相对丰度如图 2b所示.沉砂池(Gri)出水中, ARGs的相对丰度为3.12×10-6~1.19×10-3, 在一级A/O各环节中, ARGs相对丰度基本稳定在1.17×10-5~1.01×10-1, 在二级缺氧池(S-Ano)中, ARGs相对丰度下降0.4~1.4 logs, 这与该环节生物量大幅上涨有关.随后, ARGs相对丰度上升, 在沉淀池中为6.76×10-4~8.42×10-2, 比初始沉砂池丰度高出1.3~2.3 logs.可见, 升级A/O工艺不仅未能有效削减ARGs, 反而增加了出水中微生物的整体抗性水平.Rafraf和Lee等均观察到污水处理厂生物处理过程中编码对β-内酰胺类、四环素类、磺胺类和氟喹诺酮类耐药性的ARGs的相对量(基因拷贝/ 16S rRNA基因拷贝)显著增加(Rafraf et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017).

3.2 污泥中ARGs分布污水处理厂各工艺段污泥中9种ARGs的绝对丰度如图 3a所示, 9种ARGs在污泥中均被检出, 其绝对丰度为5.93×107 ~ 3.42×1011 copies·g-1.各类ARGs含量顺序为:磺胺抗性基因>喹诺酮抗性基因>大环内酯抗性基因>四环素抗性基因.污泥中磺胺抗性基因始终保持很高的绝对丰度, sul1(3.61×1010 ~ 9.79×1010 copies·g-1), sul2(1.23×1011 ~3.42×1011 copies·g-1).这可能是由于sul1和sul2是位于质粒上的基因, sul1通常与I类整合子相关联(Shing et al., 2007), sul2通常定位于较小的非接合型质粒(Enne et al., 2002)或较大的可移动多重抗性质粒上(Heuer et al., 2007), I类整合子等可移动元件是ARGs水平基因转移的重要途径, 因此sul1和sul2的定位属性利于其水平基因转移, 从而有助于其在环境基质中的广泛传播.

|

| 图 3 各工艺段污泥中ARGs的绝对丰度(a)和相对丰度(b) Fig. 3 Absolute abundance (a) and relative abundance (b) of ARGs in sludge samples of each process |

喹诺酮抗性基因gyrA(3.87×1010~ 6.87×1010copies·g-1)在各工艺段污泥中始终高于parC(1.57×1010~ 6.36×1010copies·g-1).对于两种大环内酯抗性基因, ermF含量始终高于ermA, 且保持2 logs的差别.tet A、tet C、tet M是活性污泥处理中常见的四环素抗性基因(Zhang et al., 2009), 其在污泥中的绝对丰度分别为5.93×107~ 8.07×108、4.63×108~ 7.46×109、3.69×108~ 2.61×109 copies·g-1.tetC也是一种位于质粒上的四环素抗性基因, 其绝对丰度在污泥中保持较好的稳定性(Chancey et al., 2012).

总体看来, 在一级厌氧池(F-Ana)与沉淀池(Sed)污泥中ARGs绝对丰度略高, 为8.07×107~ 3.42×1011copies·g-1, 而缺氧池及好氧池污泥中各类ARGs的绝对丰度基本稳定.这与污水厂的工艺条件有关, 在一级及二级A/O段中好氧池污泥内回流到缺氧池, 二沉池污泥回流到一级厌氧池, 污泥回流导致了相似的微生物群落, 而微生物群落组成与ARGs丰度有着密切关联(Forsberg et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017).

如图 3b所示, 污泥中ARGs的相对丰度范围为10-7~ 10-2, 低于污水中的10-6~ 10-1, 表明污泥中微生物的抗性水平略低于污水.有文献报道, 含有ARGs的微生物死亡后ARGs能够以游离状态释放(Gallori et al., 1994), 因此污泥中略低的ARGs相对丰度可能与污泥中的游离ARGs释放至污水中有关.

3.3 深度处理工艺对ARGs的去除效果为考察深度处理工艺对ARGs的去除效果, 生物处理工艺出水分别经紫外(UV)消毒和生物活性炭(BAC)工艺处理, 其基本工艺参数设置如下:水力停留时间是4 h, 处理量为500 L·h-1, UV消毒设计剂量为20 mJ·cm-2.ARGs的去除率以工艺进出水中的ARGs绝对丰度差值占进水中绝对丰度的比值求得.

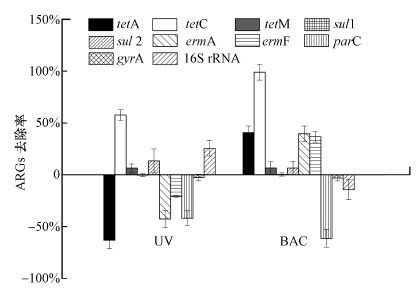

如图 4所示, UV消毒及BAC工艺对16S rRNA去除率分别为25.63%和-14.33%, 推测可能由于BAC微生物膜脱落导致出水中的微生物量增加.UV消毒对tetC、tetM和sul2的去除率分别为57.65%、6.48%和13.42%, 而对其他6种ARGs均表现出负去除.BAC工艺则能去除更多的ARGs种类, 除parC、gyrA丰度升高外, 其余7种抗性基因的去除率为0.3%(sul1)~ 99.1%(tetC).可见, BAC工艺对ARGs的去除效果优于UV消毒.

|

| 图 4 UV和BAC工艺中ARGs的去除率 Fig. 4 Removal rate of ARGs by UV disinfection and BAC process |

UV对于ARGs的去除原理主要是使ARGs形成嘧啶二聚体(Guo et al., 2019), 但污水中的背景污染物及色度导致达到ARGs灭活需要的UV剂量较高.Chen等的研究结果发现, 紫外光强为1 mW·cm-2的消毒工艺对生活污水进行深度处理, 出水中四环素抗性基因、磺胺抗性基因和一类整合子基因intI1丰度仅降低了0.3~0.7 log(Chen et al., 2013).BAC对ARGs的去除主要通过吸附作用实现, 活性炭可将含ARGs的抗性细菌吸附于表面, 并且活性炭表面形成的生物膜对ARGs也有一定的截留作用(Zhu et al., 2018).Hu等的研究发现经过活性炭处理后, 饮用水中总ARG减少0.1log (Hu et al., 2019).Guo等对位于长江三角洲的饮用水处理厂的调查发现, 一个水厂BAC出水中的ARGs低于定量PCR检测限, 而在另外两个水厂中, BAC出水中的ARGs反而有所增加, 推测对ARGs去除效果的差异可能与不同水厂BAC中的细菌群落结构不同有关(Guo et al., 2014).

4 结论(Conclusions)各工艺段污水及污泥中9种目标ARGs均被检出, 升级A/O工艺未能有效削减ARGs, 生物出水中ARGs的绝对丰度与进水相当, 而相对丰度提高1.3~2.3 logs;处理工艺沿程污泥中ARGs丰度基本稳定, 污泥中微生物的抗性水平略低于污水;BAC工艺对ARGs的去除效果略优于UV消毒, 但两种工艺均未能实现ARGs有效削减, 针对ARGs去除的深度水处理工艺有待进一步研究.

Aminov R I, Garrigues-Jeanjean N, Mackie R I. 2001. Molecular ecology of tetracycline resistance:Development and validation of primers for detection of tetracycline resistance genes encoding ribosomal protection proteins[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 67(1): 22. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.1.22-32.2001 |

Chancey S T, Zaehner D, Stephens D S. 2012. Acquired inducible antimicrobial resistance in Gram-positive bacteria[J]. Future Microbiology, 7(8): 959-978. DOI:10.2217/fmb.12.63 |

Chen H, Zhang M. 2013. Effects of advanced treatment systems on the removal of antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants from Hangzhou, China[J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(15): 8157-8163. |

Chen J, Yu Z, Michel F C, et al. 2007. Development and application of real-time PCR assays for quantification of erm genes conferring resistance to macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramin B in livestock manure and manure management systems[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 73(14): 4407-4416. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02799-06 |

Czekalski N, Diez E G, Buergmann H. 2014. Wastewater as a point source of antibiotic-resistance genes in the sediment of a freshwater lake[J]. Isme Journal, 8(7): 1381-1390. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.8 |

Du J, Ren H, Geng J, et al. 2014. Occurrence and abundance of tetracycline, sulfonamide resistance genes, and class 1 integron in five wastewater treatment plants[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 21(12): 7276-7284. DOI:10.1007/s11356-014-2613-5 |

Enne V I, Bennett P M, Livermore D M, et al. 2004. Enhancement of host fitness by the sul2-coding plasmid P9123 in the absence of selective pressure[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 53(6): 958-963. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkh217 |

Forsberg K J, Patel S, Gibson M K, et al. 2014. Bacterial phylogeny structures soil resistomes across habitats[J]. Nature, 509(7502): 612. DOI:10.1038/nature13377 |

Gallori E, Bazzicalupo M, Dal Canto L, et al. 1994. Transformation of Bacillus subtilis by DNA bound on clay in non-sterile soil[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 15(1): 119-126. |

Guo M-T, Kong C. 2019. Antibiotic resistant bacteria survived from UV disinfection:Safety concerns on genes dissemination[J]. Chemosphere, 224: 827-832. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.004 |

Guo X, Li J, Yang F, et al. 2014. Prevalence of sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes in drinking water treatment plants in the Yangtze River Delta, China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 493: 626-631. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.035 |

Heisig P. 1996. Genetic evidence for a role of parC mutations in development of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli[J]. Antimicrobial Agents And Chemotherapy, 40(4): 879-885. DOI:10.1128/AAC.40.4.879 |

Heuer H, Smalla K. 2007. Manure and sulfadiazine synergistically increased bacterial antibiotic resistance in soil over at least two months[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 9(3): 657-666. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01185.x |

Hu Y, Zhang T, Jiang L, et al. 2019. Occurrence and reduction of antibiotic resistance genes in conventional and advanced drinking water treatment processes[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 669: 777-784. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.143 |

Koike S, Krapac I G, Oliver H D, et al. 2007. Monitoring and source tracking of tetracycline resistance genes in lagoons and groundwater adjacent to swine production facilities over a 3-year period[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 73(15): 4813-4823. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00665-07 |

Lee J, Jeon J H, Shin J, et al. 2017. Quantitative and qualitative changes in antibiotic resistance genes after passing through treatment processes in municipal wastewater treatment plants[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 605-606: 906-914. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.250 |

李奥林, 陈吕军, 张衍, 等. 2018. 抗生素抗性基因在两级废水处理系统中的分布和去除[J]. 环境科学, 39(10): 1-11. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-1212.2018.10.001 |

李超, 鲁建江, 童延斌, 等. 2016. 喹诺酮抗性基因在城市污水处理系统中的分布及去除[J]. 环境工程学报, 10(3): 1177-1183. |

Li D, Yu T, Zhang Y, et al. 2010. Antibiotic resistance characteristics of environmental bacteria from an oxytetracycline production wastewater treatment plant and the receiving river[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 76(11): 3444. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02964-09 |

Li J, Cheng W, Xu L, et al. 2015. Antibiotic-resistant genes and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the effluent of urban residential areas, hospitals, and a municipal wastewater treatment plant system[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(6): 4587-4596. DOI:10.1007/s11356-014-3665-2 |

Lin L, Yuan K, Liang X, et al. 2015. Occurrences and distribution of sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes in the Yangtze River Estuary and nearby coastal area[J]. Mar Pollut Bull, 100(1): 304-310. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.08.036 |

Luo Y, Mao D, Rysz M, et al. 2010. Trends in Antibiotic Resistance Genes Occurrence in the Haihe River, China[J]. Environ Sci Technol, 44(19): 7220-7225. DOI:10.1021/es100233w |

Makowska N, Koczura R, Mokracka J. 2016. Class 1 integrase, sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes in wastewater treatment plant and surface water[J]. Chemosphere, 144: 1665-1673. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.044 |

Mao D, Yu S, Rysz M, et al. 2015. Prevalence and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes in two municipal wastewater treatment plants[J]. Water Research, 85: 458-466. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2015.09.010 |

Maurin M, Abergel C, Raoult D. 2001. DNA gyrase-mediated natural resistance to fluoroquinolones in Ehrlichia spp[J]. Antimicrobial Agents And Chemotherapy, 45(7): 2098-2105. DOI:10.1128/AAC.45.7.2098-2105.2001 |

Ng L K, Martin I, Alfa M, et al. 2001. Multiplex PCR for the detection of tetracycline resistant genes[J]. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 15(4): 209-215. DOI:10.1006/mcpr.2001.0363 |

Pruden A, Pei R, Storteboom H, et al. 2006. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants:Studies in Northern Colorado[J]. Environ Sci Technol, 40(23): 7445. DOI:10.1021/es060413l |

Rafraf I D, Lekunberri I, Sanchez-Melsio A, et al. 2016. Abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in five municipal wastewater treatment plants in the Monastir Governorate, Tunisia[J]. Environmental Pollution, 219: 353-358. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.062 |

Rizzo L, Fiorentino A, Anselmo A. 2013. Advanced treatment of urban wastewater by UV radiation:Effect on antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant E. coli strains[J]. Chemosphere, 92(2): 171-176. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.03.021 |

Rodriguezmozaz S, Chamorro S, Marti E, et al. 2015. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river[J]. Water Research, 69: 234-242. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2014.11.021 |

Shing C M, Ogawa K, Zhang X, et al. 2007. Reduction in resting plasma granulysin as a marker of increased training load[J]. Exercise Immunology Review, 13: 89-99. |

Wang H H, Schaffner D W. 2011. Antibiotic resistance:How much do we know and where do we go from here?[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(20): 7093. DOI:10.1128/AEM.06565-11 |

Zhang C M, Du C, Xu H, et al. 2015. Occurrence of tetracycline-resistant fecal coliforms and their resistance genes in an urban river impacted by municipal wastewater treatment plant discharges[J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part a-Toxic/Hazardous Substances & Environmental Engineering, 50(7): 744-749. |

Zhang J, Liu J, Wang Y, et al. 2017. Profiles and drivers of antibiotic resistance genes distribution in one-stage and two-stage sludge anaerobic digestion based on microwave-H2O2 pretreatment[J]. Bioresource Technology, 241: 573-581. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.157 |

Zhang T, Zhang M, Zhang X, et al. 2009. Tetracycline resistance genes and tetracycline resistant lactose-fermenting enterobacteriaceae in activated sludge of sewage treatment plants[J]. Environmental Science Technology, 43(10): 3455-3460. DOI:10.1021/es803309m |

Zhu Y, Wang Y, Zhou S, et al. 2018. Robust performance of a membrane bioreactor for removing antibiotic resistance genes exposed to antibiotics:Role of membrane foulants[J]. Water Research, 130: 139-150. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2017.11.067 |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40